Learning Objectives

This is an intermediate level course. After completing this course, mental health professionals will be able to:

- Define cultural efficacy.

- Identify components of cultural humility.

- Describe three dimensions of Falicov’s model, Multidimensional Ecological Comparative Approach (MECA).

- Discuss elements of a culturally informed clinical assessment, diagnosis and treatment plan.

- Explain intersectionality and its role in mental health treatment.

- Discuss role and use of cultural adaptations in evidence-based treatments.

The materials in this course are based on the most current information and research available to the authors at the time of writing. The field of multicultural psychotherapy is growing exponentially, and new information may emerge that supplements these course materials. This course material is designed to equip practitioners with a comprehensive understanding of multiple cultural identities, practice parameters, and the strengths of effective practice as well as an understanding of the potential harm inflicted on clients by less-than-competent practice. It is possible that reading about lack of awareness of multicultural factors could be triggering but those effects could be assuaged by enhanced knowledge of positive strategies for practice of effective clinical multicultural psychotherapy and by clinical consultation.

Outline

- Introduction

- Are We Culturally Efficacious?

- Guidelines For Multicultural Practice

- All Therapy and Practice Is Multicultural

- Defining “Cultural Competence”

- Training

- Graduate Training In Multicultural Practice

- Multicultural Competence

- Identities and Perspectives

- Race

- Immigration

- Socio-Economic Status and Social Class

- Language

- Religion and Spirituality

- Disability

- Intersectionality

- The Impact Of Covid

- Cultural Humility

- Cultural Formulation

- Intersectionality

- Identities

- Falicov’s MECA Theory

- The MECA Framework Includes

- Migration and Uprootings

- Ecological Context

- Family Organization

- Family Life Cycle

- Reflections

- Migration and Uprooting

- Ecological Context

- Family Organization and Family Life Cycle

- Psychotherapeutic Relationship: Strains and Ruptures

- Possible Avenues For Multicultural Interventions

- Additional Considerations - Lenses

- Cultural Countertransference

- Navigating Privilege and Oppression

- Addressing and Resolving Conflicts

- Self Awareness

- Cultural Biases: Confirmation; Implicit Bias

- Microaggressions

- Identities and Intersectionality

- Racial and Ethnic Diversity Trauma

- Dealing With Racism-Related Stress and Racial Trauma When Working With Clients Of Color

- Social Justice

- International

- Multicultural Theoretical Orientations

- Treatment Considerations

- Summary

- References

Introduction

In the ever-changing landscape of

society’s racial and cultural diversity, it is imperative that mental health

providers are equipped with the tools and knowledge to best serve diverse

groups. Having foundational knowledge of theories and concepts of

multiculturalism is critical in providing quality and effective psychotherapy.

Using a multicultural lens assists therapists in recognizing and valuing the

diversity of human experiences and the multiple ways that cultural factors can

influence an individual's thoughts, emotions, and behaviors and thus impact

psychotherapy.

The most frequent and

strongest predictor of client outcome is the therapeutic relationship. Thus,

establishment of the therapeutic alliance and identification and management of

countertransference or emotional reactivity are central factors. Apropos to the

relationship are the identities of each participant – client(s) and therapist(s) – assumptions

each makes about the other, openness to the individual cultural diversity

factors of each, self-perceptions, and perceptions and behaviors toward

clients. Therapist openness to client cultural beliefs, values, perspectives,

strengths, and resources, as well as empathic relating, are central to all

therapy. Therapist self-knowledge and awareness of personal identities, biases,

and worldviews enhance the therapeutic process. How a therapist approaches

multicultural factors, ethnicity, race, power, and privilege pave the

foundation and formation of the relationship. Interpersonal processes,

identifying and addressing strains, enhancing mutual understanding, and

initiating problem-solving all inform the therapy. There are many aspects that

can inform and strengthen the bond, enhance collaboration, and make for a respectful

process that facilitates treatment; similarly, some may hinder, feel unjust or

oppressive, or be lacking in empathy.

Therapists who

are trained in multiculturalism are better prepared to tailor treatment and address

the unique needs of clients from diverse cultural backgrounds. A better

understanding of cultural norms, values, and beliefs can influence clients' attitudes

toward mental health, help-seeking behaviors, and treatment preferences. Appropriate

multicultural training also creates opportunities to better recognize the

clinician’s own cultural biases that can impact their work.

In this program, key aspects of

multicultural psychotherapy are identified, contextualized in terms of

current research and analysis, and strategies are suggested to enhance

efficacious practice.

Are We Culturally

Efficacious?

Are

cultural identities a major factor in treatment? In a recent study it was shown

that although therapists may consider themselves culturally self-efficacious,

they generally do not even minimally address sociocultural factors or

background (Wilcox, Franks, Taylor, Monceaux, & Harris, 2020).

There was a

failure by a substantial proportion of participants. Therapists who perceived

themselves to be culturally efficacious did not even minimally address clients’

sociocultural context, demonstrating a significant disconnect between

self-perception and self- report and actual performance. Further, therapists

demonstrated denial of privilege and of oppression, simply suggesting that

sometimes dominance of some occurs. Further, tendencies toward

perspective-taking and possessing “just world” beliefs were associated with

multicultural competence. (Wilcox et al., 2020). So, a critical take-away is to not simply self-assess cultural efficacy generally but rather to consider

specific components and behaviors that comprise such efficacy.

It is also

important for the clinician to be self-aware of one’s cultural frame and

behaviors as one conducts clinical work. Our self-assessment is often not as

accurate as we believe it to be, and often differs markedly from observer

ratings. With this information, self-assess how often you use multicultural

case conceptualization. Specifically, to what extent are culture and context

significant components in your case conceptualization.

Given the important premise

that all clinical practice is multicultural, clinicians need to have

specific strategies to imbue their worldviews in their thinking,

conceptualizations, treatment planning, interactions, and relationships. Both

clinical practice and clinical supervision are cultural encounters (Falicov,

2014).

How does one strengthen one’s

multicultural practice acumen? Concern has been expressed about impact on

clinicians of the devaluation of field practicum and the disconnect between

academia and the field experience (Giddings, Cleveland, & Smith, 2007),

potentially leading to inadequate or harmful clinical practice. Substantial

evidence of the existence of harmful supervision during the training trajectory

has been revealed (Coleiro, Creaner, & Timulak, 2022) after Ellis et al.’s

(2015) shocking finding of high rates of inadequate and harmful clinical

supervision during the training trajectory. And if harmful clinical supervision

occurs, it will directly and adversely impact clinical practice. Note that in

harmful supervision, both clients and supervisees-in-training are harmed.

Guidelines for Multicultural Practice

It is critical for

practitioners to be prepared to approach multiculturalism intentionally and

systematically as a part of practice and to have requisite knowledge, skills,

and attitudes to initiate and maximize efficacy of the cultural encounter in

the frame of multicultural practice. A first step is to consider the concept of

worldviews.

Worldviews are sets of

attitudes, beliefs, assumptions, stories, expectations about the world and

social realities – and these inform our every thought and action. They impact

what we attend to, how we respond, and our attitudes and behavior toward

clients and our clinical work. As a clinician, it is critical to be self-aware

and open to input and consideration of how our own early life experiences and

identities form our expectations and behavior toward clients. From the very

onset of the therapeutic experience, our presentation (and if under

supervision, the supervisor’s as well) including attitudes and behavior, set

the frame for clinical work and relationship. Openness, supportive quality, and

empathy are essential ingredients. The depth and breadth of our worldviews set

the stage for our clinical practice.

When the American

Psychological Association presented revised multicultural guidelines (2017),

they refocused on efforts to address systems-level change rather than

traditional approaches to individual-level change. Thus, multiple populations’

historical experiences including power, privilege, and oppression were to be

addressed systemically, and attention to be focused on macro levels including

racism and multiple other isms (i.e., sexism, racism); also societal

structures: economic, educational, access to adequate culturally relevant

health care, as well as social and community contexts, all addressing both

health and healthcare disparities and access. This shift in focus to

systems-level approaches has been slow to reach the mental health communities.

Think about a client you are

currently working with or worked with previously. Before you met them for the

first time, consider how a combination of your brief information from the

client and your own life experience influenced your thoughts about how the

client would present for the first session. Reflect on how accurate your

expectations were. And think about what factors were operative in your thoughts

about how they would present. Examples could be previous clients, referral

question(s), phone screening information, and assumptions based on all of

those.

To further reflect on these

concepts, let’s review the following example.

Consider an adolescent who was referred for depression. The 14-year-old girl was not

eager to be in therapy, but her mother insisted. The therapist was unsure how

to deal with a reluctant client but began by encouraging her to identify what

was going well for her. The therapist wanted to identify three goals but the

youth was non-responsive and said therapy was “stupid.” Then the therapist gently

asked her about school and home. The client disclosed that she was at a new

school and kids at this school were really different from her. The therapist

encouraged her to talk about how they were different, and the client

said that she is Latina and most of them are not. The therapist explored that with

her, and discussion turned to her break-up with her boyfriend, worry about her

grades, annoyance with her brother, worry about her upcoming birthday, her

grandmother’s efforts to control it, and her feeling overwhelmed. She started

to say “quince …” and then stopped and asked the therapist if she even knew what

a quinceanera was. The therapist did, asked her a few questions about her many

preparations for it, and then encouraged the client to tell her specifically

what her worries were. Further discussion resulted in identifying several goals

for treatment, both immediate and longer-term ones, as they related to both the

celebration and her worries about school performance, isolation, and lack of

friends in her new school. The client asked the therapist how she knew so much about

“quince” and the therapist told her she had gone to school with several girls

growing up who had had one.

All Therapy and

Practice is Multicultural

Generally, in training

therapists studied “multicultural competence” in preparation for conducting

excellent therapy and assessment. Increasingly, concern turned to the inference

by some that “competence” was perceived as an endpoint one could achieve and

thereafter remain confident in one’s knowledge without ever learning anything

more. However, it is increasingly clear that there IS no endpoint and that the

components of “competence” – knowledge, skills, and attitudes – are ever-evolving,

and that there is no end to learning, experiencing, understanding, relating,

and integrating.

Next, researchers turned to

Multicultural Orientation (Owen, Tau, Leach, & Rodolfa, 2011), referring to

philosophy, values, and beliefs about the importance of multicultural factors

including racial and ethnic identities, and the clients’ cultural background in

the context of those of the therapist, and how one integrates all of those into

the conduct of assessment and intervention with the client(s). Importantly,

attention was focused on not simply knowledge, but on attitudes and skills.

These are essential, as therapy is anchored in relationship – which is comprised

of the working alliance, the “real” relationship, and

transference/countertransference or emotional reactivity, and is anchored in collaboration, which implicitly requires goals and tasks for therapy shared between the client

and therapist and requires therapist genuineness. When clients viewed their

therapist’s multicultural orientation positively, the therapist was perceived

to be more believable and credible, and client psychological wellbeing was

viewed to be more positively impacted. However, the results were not uniform

across various client ethnic and racial groups.

Defining Cultural Competence

While there is agreement

about the role and importance of considering culture in assessment, diagnosis,

and treatment, there remains a challenge in coming to consensus on defining

exactly what “cultural competence” is and how to achieve it in psychotherapy. A

2010 literature review that compared the various conceptualizations and

definitions of cultural competence across varied disciplines in healthcare

including psychology and social work found a lack of consensus regarding an operationalized

definition or concept of cultural competence. The review revealed that across

the varied models of cultural competence there was disparate emphasis on what

was considered to be the essential components of multicultural counseling.

Across the different models

of cultural competence, the authors did however identify four common themes

that can be used to develop a framework for providing effective clinical

services with clients of diverse cultures and backgrounds:

1)

awareness of one's own cultural beliefs and biases;

2) understanding of the client's cultural background;

3) knowledge of culturally appropriate interventions; and

4) development of cross-cultural skills.

Any therapist preparing to

work with diverse populations should prepare themselves to gain knowledge and

awareness across these four domains (Huey, et al., 2010).

Knowledge, skills and

attitudes are relevant and essential. Knowledge and understanding of one’s

personal biases, privilege, and assumptions; recognizing, respecting, and

honoring clients’ worldviews through inference and action; and being responsive

and aware of clients’ worldview and realities are all essential. Attitudes may

be implicit. Thus, engaging in reflective practice, ongoing training and

supervision, and being open to feedback and self-reflection with respect to

metacompetence (openness and thoughtfulness about what one knows and does not

know), self-critiquing, and being genuinely open to input and feedback – even

though it may be difficult to hear – are all essential components of effective

multicultural practice.

And remember there is NO

ENDPOINT to cultural competence: It is evolving and changing with experience

and with new knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

Training

Graduate Training in Multicultural Practice

Generally, attention to multicultural

competence and cultural humility in graduate training may have been limited and varied as a function

of when and where one received their training. Collins, Arthur, Brown, &

Kennedy (2015) studied student perspectives on graduate training in

multiculturalism and social justice. They identified competencies

facilitated and those in which barriers were encountered. Facilitated were:

- Developing

a culturally sensitive relationship that included accepting and respecting

cultural differences, inquiry about client’s culture, critical nature of

building a trusting environment, identifying and balancing power differentials;

- Awareness of others’ culture, balancing curiosity with respect;

- Building a trusting environment while respecting client worldview and working

collaboratively with them to achieve outcomes, as clients are the experts on

their culture and personal issues; and

- Awareness and need to balance power

differentials and not imposing personal worldviews and realities on clients

which precipitate relationship ruptures.

They described the process of

relationship-building scaffolded from their own understanding of their own

personal biases, privilege, and cultural assumptions and honoring clients’

worldviews. Barriers were student personal, interpersonal, or contextual

factors that blocked or interfered with facilitating factors. These included:

- Student lack of willingness or interest often predicated on previous negative

experiences;

- Resistance to acknowledgement of privilege or bias;

- Holding incompatible

values or views such as not being able to combat learned helplessness of

clients or disapproval of clients refusing some aspects of treatment; and

- Lack of

competence in general regarding cultural issues, powerlessness in the system, an

oppressive or discounting system or administration, or lack of resources.

Critical

questions include how to create a training environment of cultural humility? How

do each of us model reflection, acceptance, and openness to acknowledging our

own privilege, bias, and worldviews – and how do we demonstrate this in our

clinical practice?

Also, whose

perception counts? In a meta-analysis, client perceptions of multicultural

competence correlated with client outcomes, but therapist self-perceptions of multicultural

competence did not (Soto, Smith, Griner, Rodriguez & Bernal, 2018). They

described the use of cultural adaptations including holistic/spiritual

conceptualization of wellness and engaging in cultural rituals. Areas of

cultural adaptation included: language, use of and content of metaphors,

general content, goals, methods, and the context. Consider your own use of

cultural adaptation and how you enact it. Examples include respectful inquiry

about cultural meaning, spirituality in the context of the presenting issues or

solutions, harmony, and reflective practice including indicating if the

therapist does not understand a concept or practice. However, likely as a

result of their level of acculturation, children benefit less from cultural

adaptations (Huey & Polo, 2008).

It is suggested

that although therapists cannot be competent in every client identity or

attribute, they could be aware of, open to, and attempting to adapt treatment

to align with the salient intersecting identities, those valued most by the

client (e.g., religious, culture-specific) (Soto et al, 2018).

Another question

is how accurate is one’s own self-assessment? And how effective is one

multicultural course without integrated supervision and ongoing support?

Self-assess on your own training during the graduate trajectory and consider

the strengths and barriers presented above as well as the evolution of practice

and research in the past decade. Remember that your own active efforts to

self-assess enhance your self-knowledge and thus your competence.

Multicultural

Competence

Recognition must

exist that there are multiple factors in the provision of multiculturally

relevant therapy. This includes knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Provision of

therapy and assessment in a respectful, knowledgeable, and culturally competent

manner are essential. There is significant recognition that psychotherapy must

be culturally competent and occur through the lens of cultural humility. However,

clinicians may find themselves unclear or challenged to do so. Examination of

one’s attitudes, beliefs, skills, knowledge, and previous life experience is

imperative. Considering one’s assumptions about therapy, therapeutic

relationships, psychotherapy models, multicultural psychotherapy, values, and

biases are all essential.

Consider the

grounding principles of the APA’s Guidelines on Race and Ethnicity (APA, 2019):

articulating the critical and ubiquitous influence of ethnicity, race, and

related issues of power and privilege with the understanding that social

justice is inherent to racial and ethnocultural responsiveness. It is essential

for clinicians to be self-aware and proactive in discussion of race and racial

identity. This includes attending to power differentials related to race in

professional interactions and in relationships, minimizing detrimental effects

of unconscious, implicit bias. Race and ethnicity are sources of meaning and

context. Some possible steps provided in the guidelines are:

- modifying intake forms to address more complex meanings and

understandings of race, ethnicity, and intersectionality;

- regularly considering the racial and ethnic climate of the setting; and

- developing procedures to ensure that racial and ethnocultural influences

are directly addressed.

When race is

avoided, the avoidance interferes with relationships, promotes social distance,

and may be inferred to be (or is) implicit bias or implicit prejudice or

represents a set of negative attitudes. These may be manifest as social

distance, presumed prejudice, implicit attitudes, micro or macroaggressions

that are expressed or experienced, and internalized racism. Implicit bias is

automatic and unintentional, and results in assumptions, preferences,

aversions, or behavior that results in (unintended) assumptions and actions.

For example, when a therapist is more affiliative and responsive to someone

with a common name rather than a less usual name that may be associated with a

particular ethnicity, or making assumptions about a group or individual based

only on race. All of these prevent connection and harm the therapeutic

relationship. Race and ethnicity are also associated with experiences of

oppression, privilege, and power. Avoidance of the topics may lead to

assumptions of disrespect and generally undermine relationship and the

framework of social justice and fairness.

The first of these APA

guidelines (2019) is to “strive to recognize and engage the influence of race

and ethnicity in all aspects of professional activities as an ongoing process”

(Guidelines, APA, 2019, p. 9). With value attached and recognition of

importance, the clinical guideline sets the stage for discussion and mutual

understanding. Guidelines three and four entail striving for awareness of own’s

own positionality (and identities) with relation to ethnicity and race, and

addressing social inequities and injustices.

Proactive discussion includes

engaging in reflective practice including exploration of worldviews and social

positions, all of which are impactful on the presenting problem and the therapy

that ensues. Thus, it is imperative that clinicians continuously engage in

learning about these aspects of culture.

Identities and Perspectives

Race

Black persons are more likely

than Hispanics or Asians – and much more likely than White persons – to say

that their race is central to their identity. According to the Pew Research

Center, about three-quarters of Black adults say being black is extremely or

very (74%) important to how they think of themselves; 59% of Hispanics and 56%

of Asians say being Hispanic or Asian, respectively, is important, and about

three-in-ten in each group say it’s extremely important. In contrast, just 15%

of Whites say being white is very or extremely important to how they think of

themselves.

(pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/04/09/race-in-america-2019/)

Racial and ethnic identity

thus are central to all aspects of self, although the extent is variable;

discrimination and racism negatively impact mental health processes and

outcomes. Race itself is complex, as it is a social construct that relates to

skin color, facial features, hair texture, and body shape (Harrell &

Sloan-Pena, 2006).

BIPOC (Black and Indigenous

People of Color) individuals are less likely to seek therapy, and when they do,

they are more likely to terminate therapy early (Owen et al., 2017). The

multicultural competence model proposed that therapists are expected to learn

culturally relevant knowledge, be open to challenge their own beliefs regarding

marginalized populations (awareness) and use culturally sensitive interventions

and skills.

Research has revealed that

when race or racism comes up in therapy, regardless of their own race

therapists often respond to BIPOC clients with denial, avoidance, or other

signs of cultural discomfort. Specifically, when Black clients bring up anti-Black

racism in session, particular responses occur. Bartholomew and colleagues

identified four such possible therapist responses:

(a) wanting

to move beyond strict acknowledgment to ensure acknowledgement of pain and

affirmation of experience;

(b) being present in the moment and drawing personal awareness into that moment;

(c) turning inward and engaging with one’s own emotional responses including

empathy with those experiences; and

(d) I am versus I should: proactive and reactive comfort including recognition

of pain and reacting to it authentically.

Therapist comfort is an

essential aspect that increases the likelihood such disclosure and discussion

occur. More specifically, therapists’ level of cultural comfort when discussing

anti-Black racism with Black clients may be based on their own racial

experience or emotions linked to personal racial beliefs, identities, and their own

life experience growing up (Bartholomew et al., 2021).

Use of the concept of the

ecological niche (Falicov, 2014) – consideration of multiple cultural locations

and their intersectionality – is useful in addressing client and therapist

identities. Harrell (2014) suggested considering familial and community racial

socialization including the salience of race, how much identification with the

racial group exists, meanings, beliefs, and judgments about race. Even if

client and therapist share the same racial group, intersectional multicultural

identities need to be factored in. Misunderstandings may occur if one minimizes

race or alternatively excludes other identities and factors, focusing only on race.

Harrell (2014) suggests ongoing reflective practice in order to understand the

multiple layers of sociopolitical, interpersonal, and intrapersonal meaning of

race for the individual and their family, regarding the referral question and

the context.

Immigration

Migration is often a

neglected multicultural consideration. At least 13.6 percent of the U.S.

population is comprised of immigrants (Migration Policy Institute, 2023).

However, generally, it is seldom discussed in clinical practice or in clinical

supervision. Falicov (2014) highlighted the complexity of experiences in

immigration, and the impacts that are often longstanding and profound. She

urges consideration of preimmigration, migration, and postmigration

considerations in the psychosocial assessment of clients. Further,

intersectionality with socioeconomic status, race, gender, gender identity,

age, generation, and developmental status at immigration; country of origin

(and its proximity, reason for migration including trauma); the process of

immigration, whether voluntary or forced; internal or refugee status, impacts,

and current immigration status should all be considered as well. Also important

is connection with family and friends in the country of origin through

telecommunication. Falicov urges a strength-based approach, considering losses

in the context of resilience, gains, and triumphs. She also emphasizes cultural

humility and intersectionality in a social justice frame.

Understanding family and

individual specific stressors, coping, and strengths is essential. Falicov

distinguishes between coaxed and unprepared migrations, those that were planned

and those that were very much in response to an event, often traumatic. Some of

the general issues to be discussed include a genogram of family in the U.S. and

in the home country, relationships, and emotional responses, losses, including

of employment, professional, or educational status, how family members are

learning the new language (which may rely on children who are learning the new

language at school and thus are potential translators for the family),

migration narratives, and whether children and family members are aware of any

or all aspects of the above.

Falicov uses the MECA (Multidimensional Ecosystemic Comparative Approach )

framework including ecological context (e.g., living conditions, school access,

limits on upward mobility, financial stressors, physical, psychological, and

cultural trauma), family life cycle (e.g. loyalty to family of origin, losses

of other generational influence, support), migration/acculturation status

(legal status, language acquisition and fluency), and family organization

(bonds with family members locally in in country of origin, family hierarchy

changes precipitated by migration including employment, roles, language

fluency). Further, Falicov describes interventions and therapist roles as a

function of stage of migration. Initially, the therapist deals with crises, and

helps to address and sometimes restore ecological order within the family. An

important aspect is engaging in self-reflection – by the therapist (and the

supervisor if there is one) to deconstruct and contextualize through the lens

of the personal experience of immigration of each.

Thus, it is essential for the

therapist to be self-aware of the impact of their own life experience (or

influences on their perspectives on immigration and acculturation) on their

clinical work with the family. Examples include a therapist who shares language

fluency with the family, although bearing in mind that language fluency does

not imply cultural competence or complete understanding of the client

experience. In addition to language, consideration of religion, spirituality,

family dynamics, ethnic identity, perception of and aspects of discrimination,

and understanding causal factors leading to illness, all viewed through a frame

of cultural humility, respectful caring, and strength-based approach.

In cases of forced migration,

an involuntary displacement and a crisis and upheaval of life expectations with

resulting barriers and stigmatization, cultural humility is essential (Adams

& Kivlighan, 2019). A high frequency of misdiagnosis and misunderstanding

occur when addressing the general physical and psychological consequences of

such migration that occurs generally with no warning or preparation.

Sensitivity to cultural and situational aspects of emotional expression,

exploration of harassment and prejudice, dynamics of resettlement and emotional

impact, and general empathic responding are essential.

Socio-economic Status

and Social Class

Socio-economic status and

social class include not simply income but educational attainment, financial

security, and subjective considerations, as well as one’s own and others’

perceptions of economic status, social status and social class. Social class is

more than income, education and occupation, and includes economic resources,

education, and occupation as well as prestige and power (summarized in Fouad

& Chavez-Korell, 2014). The APA guidelines for psychological practice for

people with low income and economic marginalization address economic

marginalization (APA, 2019).

In their resolution on

poverty and socio-economic status (SES), the American Psychological Association

(2023) identified the increasing gap between upper and lower SES, the

devastating personal and financial repercussions of the confluence of COVID and

an economic downturn, and the devastating impact of the intersection of low SES

and multiple minoritized identities, historical and systemic discrimination,

biased laws and resultant economic inequality. The resolution includes a

summary of the current research on the impact of poverty, intersections with

multiple identities, and impact on human rights. Economic marginalization

results in limited access to supports, resources, and opportunities in life,

which limit educational, physical and mental health, achievement, and general

quality of life.

Understanding not simply the

status or the economic numbers, perhaps represented by fees, but the need for

mental health providers to approach these with cultural humility, the therapist

needs to frame impacts on the presenting problems and on the possible treatment

options, to address specific needs.

Language

Over 350 languages are spoken in the U.S. according to the

2018 U.S. Census. A challenge to mental health is providing competent services

to those who seek them. 41 million people spoke Spanish at home. Even if the

therapist “speaks” Spanish, they may find they are less equipped to deal with mental

health issues or the language specific to those. Bilingual services are

severely underrepresented and much needed.

For example, it is

important to know that both therapists and clients report reverting to their

native language for emotionally intense disclosures or discussions, often

referred to as “code-switching” or “language switching” –especially if the

memories were encoded in the native language.

Valencia-Garcia and Montoya

(2018) state that although the need for bilingual therapists is acute, there is

still inadequate training – even though the U.S. census predicts 30% of the

population will be Latino by 2050. Common errors are assumptions that if a

supervisee or therapist has a Spanish surname, or says they speak “some”

Spanish, that they will be fluent and able to conduct therapy bilingually in

Spanish or any of the approximately 400 languages spoken in the U.S. Professional

fluency is distinct from conversational fluency. Further, a very small minority

of bilingual therapists have received bilingual supervision during their

training

A result is that ethnic and

racial minority students who are bilingual find themselves carrying the burden to

provide therapy in a language other than English with no training in therapy or

assessment in their native language or language they have studied, nor have

they been supervised either in the client language or by a bilingual

therapy – often due to the fact that the student is the only person on the staff

who speaks the language of the client. Or a translator is provided who is a

family member or office worker who has no training in translation and no

clinical training to understand relevant communications or to translate them

accurately, and may have significant emotional response or involvement in the

family situation. This is an area of significant concern and deemed essential

for ethical outcomes.

Having a shared language is

generally a great strength for therapeutic rapport, but bilingualism should not

be viewed as synonymous with cultural competence or knowledge and attitudes,

but it is clearly a great strength. Consultation is indicated and essential

when conducting evaluations (often high-stakes) or interventions to understand

culture and nuance. The value of bilingual therapy with Latino clients was

studied. Bilingual therapy was associated with:

(a)

Enhanced expression and understanding;

(b) An affirmative experience;

(c) Facilitating therapeutic processes;

(d) Utility of a therapist bilingual orientation, and;

(e) Strengthening the therapeutic relationship (Perez-Rojas et al., 2019).

Religion and Spirituality

Although often neglected or

frankly ignored by therapists, religion and spirituality shape personal

experience and are an essential aspect of worldview. They may also be a source

of strength, comfort, and hope. Or may be a source of distress, negative affect,

or anger (Vieten & Lukoff, 2022). However, these subjects are rarely

discussed or addressed in training or in clinical practice. Self-awareness and

-appraisal are critical for clinicians: considering one’s own faith commitment

and attitudes toward religion and spirituality. Gallup polls reveal that the

vast majority of the U.S. population report religion is “very or fairly”

important; in contrast, mental health professionals may view religion as much

less important (Shafranske, 2016).

Approaching religion and spirituality with an attitude of respect and openness

and competence is a professional competence, and neglecting to do so reflects a

deficit in cultural competence (Vieten & Lukoff, 2022). Vieten and Lukoff

(2022, p. 32) described and proposed 16 religious and spiritual competencies

for clinical practice. Attitudes and beliefs included demonstrating empathy,

respect, and appreciation for clients from diverse spiritual, religious or

secular backgrounds and affiliations; having awareness of how one’s own

spiritual and/or religious background and beliefs may influence their clinical

practice; and attitudes, perceptions, and assumptions about the nature of

psychological processes. Knowledge includes knowing that diverse forms of

spirituality and/or religion exist, and exploring spiritual and/or religious

beliefs, communities, and practices. Skills include helping clients explore and

access their own spiritual and/or religious strengths and resources.

Expanding upon cultural

humility through the lens of religion and spirituality, Davis and colleagues

add essential components of therapist civility, a neglected aspect, with

empathy, an affective stance. It includes openness; willingness to recognize

and explore different beliefs and perspectives; awareness of one’s own values,

beliefs, worldviews, strengths, and areas in development; an egalitarian

worldview; openness to diversity and differences, including in values and

self-reflective capability; awareness and proactive responding to inequality

and prejudice (Davis et al., 2021). An important aspect is how clients perceive

their therapists’ cultural humility toward religion and spirituality.

Although they identified their

findings as specific to correctional work, Gafford and colleagues describe risk

and strengths that are more generally applicable for therapists. Risks include

exhibiting moral superiority, discounting the client’s religious awakening or

beliefs, viewing faith as a discounting of responsibility, lacking cultural

comfort with client identities, and viewing religion as a defense or barrier to

treatment. Strengths include openness to client cultural discussions,

regulating negative feelings perhaps related to previous clients, exploring

cultural values, and openness to discussion of a religiosity-respectful process

(Gafford, Raines, Sinha, DeBlaere, Davis, Hook & Owen, 2019)

Disability

Disability is a lasting

physical or mental impairment that significantly interferes with an

individual’s ability to function in one or more central life activities, such

as self-care, ambulation, communication, social interaction, sexual expression,

or employment.

Disability is a broad concept

used to describe the interaction of physical, neurodivergent, psychological,

intellectual, and socioemotional differences with personal and environmental

factors including attitudes, cultural beliefs, legal and economic policies,

transportation, access, etc. A result may be disability stigma (Balva &

Tapia-Fuselier, 2020). Generally, training for therapists on disability ranges

from limited to nonexistent. And therapists are often not prepared to work with

clients with visible or hidden disabilities. Barriers for the disabled include

attitudinal, communication, physical, policy, social, and transportation

barriers.

"Ableism” is

discrimination toward and social prejudice against individuals with

disabilities. The American Psychological Association issued guidelines for

Assessment and Intervention with Persons with Disabilities (2022) that advocate

for changing ableist practices. That is, addressing and counteracting negative

stereotypes and assumptions and implicit bias which often result in

microaggressions. As lack of training and experience lead to prejudice, it is

essential for therapists to gain experience and to identify and address faulty

assumptions and bias. Recommended practices include therapist self-examination

of biases, beliefs, and emotional reactions to individuals with disabilities; and

considering implicit bias and intersectionality of race, nationality, and other

identities with disability. Since attitudes are deep-seated, self-awareness and

reflection are imperative. Strength-based approaches are indicated. Imperative

is knowledge of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (1990), the Americans

with Disabilities Amendments Act (2008); and the Individuals with Disabilities

Education Act (IDEA) (1997). Understanding the function and requirements of

reasonable accommodations is essential.

Developmental disabilities

refer to limitations in cognitive and functional abilities impacting learning,

problem solving, reasoning, planning, and in adaptive behavior such that the

individual does not acquire nor evidence skills that would be expected for

their developmental or chronological age group and would be necessary for

independent functioning as an adult. Neurodiversity refers to the shift to a

more positive, strengths-based approach to what were previously referred to as

autism, neurodevelopmental disorders, ADHD, and other behavioral differences (Fung,

2021).

Intersectionality

Increasingly it was

understood that most important is “intersectionality” or consideration of the

multiple identities of the client and therapist (and if under supervision,

those of the supervisor as well). This led to the current conceptualization and

critical component of multicultural practice, the concept of cultural humility,

openness to client diversity statuses, and recognition of the complexity of our

own status, and society’s and their intersection in relation to the client’s

identities, being respectful, open, and humble. The therapist needs to be open

to the worldviews and belief structures of the client(s) – often many within a

family constellation – and to be self-aware and monitor our own emotional

responses to difference. Further, exploration of “missed opportunities” to

discuss culturally relevant aspects of identity, behavior, and relationships in

life and in psychotherapy was introduced as there was substantial recognition

that such opportunities were frequent.

Recognition grew that client

reports of therapist behavior were more complex, multifaceted, and intersectional – these

concepts were not able to adequately address them.

Humility generally is

described as a fundamental human virtue. It is advocated in religious,

spiritual, and philosophical traditions, with adaptations and variations on

definition.

The Impact of COVID

Impact of COVID was

devastating generally and revealed dramatic health disparities for members of

racial and ethnic minority groups who had higher rates of COVID-19 positivity

and disease severity than White populations, less access to care, and had more

negative outcomes, including death. Causative factors included overrepresentation

of members of racial and ethnic minority groups in essential jobs which

increased vulnerability and exposure to COVID-19, lack of primary care access,

lack of health insurance and access to emergency care, as well as lack of

resources available in hospitals, differentially (Magesh et al., 2021). Social,

economic, and health inequities were perpetuated and exacerbated. COVID has led

to loss of beloved elders, loss of schooling or diminished schooling via

telecommunication as racial and ethnic minority students had less consistent

access, support, and connection (Falicov, Nino, & D’Urso, 2020). Mental

health needs rose as mental health resources were severely disrupted.

Recommended practices for clinicians included generally adopting an attitude of

cultural humility, focusing on identifying “emotional contagion,” identifying

impacts of systemic injustice that are likely being compounded by COVID-19, and

recognizing and addressing racial trauma in clients of color (Meyer & Young,

2021). For clinicians, moral injury occurred in that in multiple circumstances

they encountered experiences that were in conflict with their personal values,

making decisions where all options could lead to negative outcomes, sharing

pain and trauma with families, and fearing for their own safety.

Cultural Humility

Clearly, knowledge and skills

are not sufficient. The therapist must exhibit an attitude of the essential

importance of cultural humility – but simply espousing this is not sufficient;

one’s actions and attitudes must be syntonic and evident. This includes active

recognition of one’s own beliefs and biases, in value-attached and historical

context. Childhood experiences can be emblematic in our current behavior – and

may not even be noticed or recognized. Thus, a therapist may make assumptions

about a client based on their own life experience, or may have a negative

predilection toward an aspect of the client that they have not even recognized

or acknowledged. It only becomes recognized through reflection, noticing our

own behavior that is unusual or deviates from what one usually does. For

example, a client may share an identity with the therapist, for instance coming

from the same part of the country, and implicitly, without consciously

recognizing it, the therapist may be operating with assumptions based on their

OWN life experience – experiences during elementary school, values attached to

moving across the country, or multiple identity assumptions (socio-economic

status, ethnicity, race, religion, political affiliation, gender, gender

identity, sexual orientation, etc.).

“Cultural humility” is a

term introduced in 1998 by physicians Melanie Tervalon and Jann Murray-Garcia. It

entails humility and engaging in self-reflection and self-critiquing throughout

one’s client interactions and in formulations and clinical interventions. Anchored

in what we call “metacompetence,” or identifying and “knowing” what we do not

know, being humble, open, and resourceful, engaging the client in exploration

with respect and acknowledgement that the client knows their own experience

substantially more than we do. And, that we truly do not know what we do not

know. Cultural humility is both an attitude and a worldview. It has been defined

as “the ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented (or

open to the other) in relation to aspects of cultural identity that are most

important to the client” (Hook et al., 2013, p. 354).

Consider the following

dimensions of cultural humility: Accurate perception of one’s own cultural

values and other-oriented perspective incorporating respect and respectful

process, lack of superiority in attitudes or behavior, openness to feedback

(even negative) from others, awareness of judgments.

Words to describe clinical

interactions: Open, non-defensive, thoughtfulness and reflection before

determining response to culturally loaded queries or topics, respectful

curiosity, ability to question our assumptions and beliefs in a cultural frame,

markers of cultural humility.

Consider your own cultural

identities and which are associated with power; which with privilege vs.

prejudice, discrimination, oppression, in a frame of historical context. (Privilege

defined as status(es) that afford you a benefit or advantage over others [Falicov,

2014; Hook, Davis, Owen, & DeBlaere, 2017, Falender & Shafranske, 2021]).

Cultural humility entails the

specific ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is respectful and

open to the other, to their experiences, worldviews, and to aspects of their

personal cultural identity. In displaying respect, therapists do not appear

“superior,” instead having a stance of openness and acceptance of the client

and their personal experience. The therapist collaborates with the client, hears

the client’s disclosures and perspectives, and considers the uniqueness of the

client’s presentation of intersectionality, their multiple identities and their

intersections (i.e., ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, socioeconomic

status, race, religion), mindfully noting their own intersections and attending

to not inferring worldviews similar to the client’s. Key to the therapist

approach is an attitude of “not knowing” and being open to differing worldviews

and experiences that the client presents. We frame not knowing as

“metacompetence,” or being open to knowing and identifying what one does not

know. That is inclusive of being alert to areas of lesser competence, and being

open to disclosing lack of knowledge, skills, or perspective regarding a

particular area or areas.

Hook, Davis, Owen,

Worthington, and Utsey (2014) caution that rather than assuming

knowledge and understanding of diverse clients, therapists remain mindful that

we need to be aware of the limits of our knowledge of someone else’s life

experience. Cultural humility in the therapist is strongly associated with the

therapeutic alliance in that the therapist’s attitudes and values and openness

to “other” stance is strongly associated with the working relationship. In

fact, cultural humility was judged more important than therapist similarity,

knowledge, experience, and skills (Hook et al., 2014).

On a scale of cultural

humility developed by Hook and colleagues (2014, p. 357), positive items

connoting cultural humility included being respectful, open to exploring,

considerate, interested in learning more, open to seeing things from others’

perspectives, open minded; and asking questions when uncertain. Conversely,

negative exemplars included assuming one already knows a lot, making

assumptions about others, being a “know-it-all,” acting superior, and thinking

they know more than they actually do. And client perceptions of a therapist’s

degree of cultural humility were generally positively related to higher quality

of alliances with the therapist, but that was a finding that required further

study.

Cultural humility has been

described as composed of cultural humility, cultural opportunities, and

cultural comfort. The three pillars are: 1) cultural humility; 2) cultural

comfort; and 3) cultural missed opportunities. Cultural humility is defined as

the establishment of egalitarian, collaborative relationships with clients

while at the same time remaining self-aware and non-defensive regarding the

therapists’ own limitations to being other-oriented. Cultural comfort is the

level of genuine comfort one has in holding space for multicultural discussions

and conducting those in therapy. Cultural comfort has also been described as

the ways a therapist finds to be at ease, relaxed, and open when discussing

clients' cultural identities in treatment. A research finding is that client

perceptions of therapist’s cultural comfort were predictive of decreases in

psychological distress (Bartholomew, Perez-Rojas, Lockard, Joy, Robbins, Kang,

et al., 2021). Cultural missed opportunities refers to how often and how deeply

(and sincerely) a therapist explores (or misses) topics related to culture and

identity with a client (Owen, 2013; Owen et al., 2011) and lets opportunities

slip by.

Therapists who are rated high

on cultural humility and cultural comfort, and low on missed opportunities,

demonstrate better treatment outcomes generally.

The client may perceive the

therapist as having missed opportunities to discuss their cultural background,

wish the therapist had encouraged more discussion of culture and cultural

background, avoided topics related to the client’s cultural background, or

generally missed opportunities to have deeper discussions on those topics. Conversely,

the client may feel gratified that the therapist addressed, in depth, cultural

background (Owen, Tao, Drinane, Hook, Davis, & Kune, 2016).

Consider ways a therapist can

communicate cultural humility rather than communicating superiority or already

knowing. Consider again the words that can be used to describe clinical

interactions such as open, non-defensive, thoughtfulness, and reflection before determining responses to culturally loaded queries or topics, respectful

curiosity, ability to question our assumptions and beliefs in a cultural

frame – are all markers of cultural humility. Think about ways you communicate cultural humility.

Generally, when therapists

are culturally humble, they convey openness, respect, and interest. Both verbal

and nonverbal expressions are important.

Interestingly, depending on

context, identity salience changes. That is, one or several identities may be

salient in some situations and others in other situations. For example, one’s

religious identity would be salient when one was at a church or temple event,

the same individual’s racial identity salient when in a mental health

multicultural seminar. Less attention has been devoted to intersectionality,

which is a very important factor in understanding identities.

Davis and colleagues (2018)

proposed a multicultural orientation framework to address how cultural dynamics

influence the process of psychotherapy. That is, as theorists and researchers

have long suggested, psychotherapy relationships which include therapist

empathy and creating a working relationship with the client are inadequate

without consideration of the multicultural factors and dynamics of the client,

family, and significant others. So, focus is shifted to what is described as

orientation or how the therapist views, organizes, understands what the client says,

and how the client creates meaningfulness of the world and relationships within

it. They suggested that rather than focusing on “competencies,” which might be

perceived as inflexible, the therapist needs to be attuned to context,

behavioral change, and meaning. And the therapist does need to attend to identifying

and knowing what they do not know, which Falender & Shafranske (2021) refer

to as “metacompetence” – the ability to step back and increase awareness that one

does not know another’s experience, perceptions, or understanding … and the

therapist needs to be open to that recognition. In multicultural therapy (which

is ALL therapy), attunement to what one does not know is essential, as is openness

to that fact. The client is the expert on their own life and situation; the

therapist can assist them in multiple ways, but the client remains the expert

on their experience.

Key components of cultural

humility include respectful process, openness, and curiosity (Falicov, 2014) as

well as attending to intersectional identities of client, therapist, and if

there is one, the supervisor.

Another concept, intellectual

humility, is also essential in clinical practice. Intellectual humility is

best defined as people’s willingness to reconsider their views, to avoid

defensiveness when challenged, and to moderate their own need to appear

“right.” It is sensitive to counter-evidence, realistic in outlook, strives for

accuracy, shows little concern for self-importance, and is corrective of the

natural tendency to strongly prioritize one’s own needs. See: templeton.org/discoveries/intellectual-humility.

An additional critical

component within multicultural practice is social justice, addressing

the fair treatment and equitable status of all individuals and social groups

within a state or society. It also refers to advocacy focusing on forms of

oppression that limit access and opportunity in society as a function of

membership in socio-demographically diverse groups. It is aimed at attending to

change in societal values, policies, and practices to increase access to tools

of self-determination (derived from Goodman et al. 2004). Social justice has

been often sidelined or ignored by mental health professionals with the

exception of social workers for whom it is among their guiding principles (NASW,

2019) with articulation of equity and inclusion, spanning voters’ rights,

criminal and juvenile justice, environmental justice, immigration, and economic

justice. (See the section on Social Justice, below. )

Incorporating social justice

includes perspective-taking and consciousness-raising about differences and

inequities and addressing those; addressing power (in the therapeutic

relationship and societal impact on the client’s presenting problems);

perceptions of fairness and lack of such; and expressions of empathy, support,

and connection.

Gender, gender identity,

sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, and to some extent disability, are being

addressed and are increasingly recognized as significant identity factors in

mental health practice. However, consider multiple other identities that are

NOT being addressed or noticed in mental health, and the intersectionality of

identities. Some identities that are less addressed are religion, social class

or socioeconomic status, immigration status, education level, and language, to

name a few. Socioeconomic status relates to access to resources and power, and

positionality in the social class hierarchy. Multiple identities are

interrelated.

Cultural Formulation

Recognizing the cultural

nuances of different groups is important in order to enhance the effectiveness

of treatment outcomes. It increases the awareness and sensitivity in

understanding how different symptoms, disorders, and presenting issues may look

or manifest within and across different cultural groups. As part of a very

thorough clinical intake, the clinician must gather relevant psychosocial,

contextual and historical data that is then conceptualized within the social cultural

context of the client. Culturally informed intake and case formulation allows the

clinician to carefully consider clinically and culturally appropriate diagnoses

and treatment recommendations.

Pamela Hays’ ADDRESSING model (Hays 2001) offers a framework for clinicians to consider not

only the variables of culture to consider when gathering intake information,

and history from a client, but also strategies for self-reflection for the

clinician to consider the ways in which their own biases and cultural

identities emerge within clinical practice. ADDRESSING stands for:

- Age and

Generation;

- Developmental Disability;

- Disability (Acquired);

- Religion;

- Ethnicity and Race;

- Socioeconomic Status;

- Sexual Orientation;

- Indigenous Heritage;

- National Origin

and Language; and

- Gender.

Integrating the ADDRESSING framework into clinical

practice can lead to a cultural understanding of the client which offers the

clinician a robust case formulation that examines how social, cultural,

historical, and contextual variables are embedded within the development and

maintenance of clinical issues. An added benefit to application of Hays’ model

is that she encourages the clinician to consider not only their own cultural

factors as it relates to the multiple identities of their clients, but also

exploration of how these variables differently affect groups based on

membership in either the dominant or non-dominant group ( Hays 2022).

Below is a sample vignette which illustrates how

critical the integration of culture at time of intake is for clinicians. Please

read the vignette and then answer the questions that follow:

Jessie is a 35-year-old single male who presents for

an intake session seeking help for symptoms of anxiety and depression which are

interfering with his work performance. Jessie has difficulty sleeping at night

due to racing thoughts and has recently lost approximately 10 pounds in one

month. Jessie works as a software engineer and reports feeling overwhelmed and

stressed out by the job, which often requires long hours.

As you read the vignette, did you notice any automatic

assumptions regarding Jessie’s gender, race, ethnicity, or age? What are your

initial thoughts in terms of the assessment of Jessie’s symptoms and factors

contributing to the onset of symptoms? What might be some initial

recommendations or considerations for a treatment plan?

Now

consider that Jessie is a 35-year-old single woman and is one of few women in

her workplace. In what way does that change your conceptualization of the

workplace anxiety and any intake questions you may ask. What if Jessie is also

Jewish and there has been recent antisemitic violence in the area where her

company office is located. This vignette illustrates how therapists working

with clients from various cultural backgrounds need to understand and

appreciate the systemic, contextual and cultural differences that may impact

their clients' mental health and wellbeing.

When attending to diversity factors and in modifying

treatment to meet the needs of clients there can be assumptions about

appropriateness of evidence-based treatments

To address the role of

cultural variables on the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders, the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - IV (DSM-IV) included an Outline of Cultural Formulation to give clinicians guidance on factors

to consider that yield better understanding and consideration of the impact of

psychosocial and cultural factors on symptom presentation.

As outlined in the DSM -IV,

the Outline of Cultural Formulation (OCF) consists of five components:

1.

Cultural Identity of the Individual

What are aspects of the client’s culture, race, ethnicity, nationality that

influence the presentation of symptoms as well as the client’s beliefs about

mental illness.

2.

Cultural Explanation of the Individual’s Illness

Exploration of how the client’s cultural background informs their explanation

of the cause and contributions to their psychological distress and mental

illness.

3.

Cultural Factors Affecting the Psychosocial Environment and Levels of

Functioning

Exploration of how client’s level of functioning, interpersonal dynamics,

family relationships, and social support systems are affected by cultural

variables.

4.

Cultural Elements of the Relationship Between the Individual and the Clinician

Encourages therapist to consider similarities and differences between therapist

and client to consider if and how those factors can affect the therapeutic

relationship.

5.

Overall Cultural Assessment for Diagnosis and Care

In this last component, the clinician integrates all the pieces of information

together to develop a culturally sensitive formulation which considers how

clients will respond to treatment.

While this OCF addressed a

previously neglected aspect of diagnosis and treatment planning, there was

still a need to provide direction and guidance to therapists on developing a

cultural formulation. Authors of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Ed.(

DSM 5) were very intentional in designing a Cultural Formulation Interview

(CFI) that expanded upon the OCF by detailing specific questions to elicit

information related to the client's cultural factors. The CFI defines culture

as the following (Aggarwal & Lewis-Fernandez, 2020):

Culture

refers to systems of knowledge, concepts, rules, and practices that are learned

and transmitted across generations. Culture includes language, religion and

spirituality, family structures, life-cycle stages, ceremonial rituals, and

customs, as well as moral and legal systems. Cultures are open, dynamic systems

that undergo continuous change over time; in the contemporary world, most

individuals and groups are exposed to multiple cultures, which they use to

fashion their own identities and make sense of experience.

The core CFI is a structured

interview comprising 16 questions that are organized around the five domains of

the OCF (Aggarwal et al. 2013).

The core CFI is organized into

four sections:

1) cultural definition of the problem;

2) cultural perceptions of cause, context, and support;

3) cultural factors affecting self-coping and past help-seeking; and

4) cultural factors affecting current help-seeking (Aggarwal & Lewis-Fernandez,

2015).

In addition to these four sections, there are also three supplemental domains

that can be appended to cultural formulation interviews to further assess the

socio-cultural factors relevant to an individual’s mental health functioning

(Jarvis et al, 2020):

1.

Cultural Strengths and Resilience

Within this domain the therapist identifies cultural traditions, rituals and

routines that serve as sources of support and can be integrated into treatment

planning to promote wellness and recovery.

2.

Cultural Challenges or Barriers to Care

This domain provides direction on asking questions about cultural factors or

beliefs about mental health that may interfere with accessing or receiving mental

health care.

3.

Cultural Identity of the Clinician

This supplemental domain has the clinician reflect on their own cultural

background and how it might impact the therapeutic relationship. Mental health

providers consider cultural biases as well as present ideas and techniques for

promoting cultural humility within the therapeutic setting.

There are also twelve

additional supplementary modules to the CFI which offer a more in-depth exploration of the five domains as well as considering

the specific needs of unique treatment populations such as children, older

adults, immigrants, and/or refugees.

A third component of the CFI

is an informant version of the CFI that allows the clinician to gather

collateral information and obtain the perspectives of family members and social

support systems of the CFI. As a clinical intake tool, the CFI assists the

clinician by providing a thorough, systematic, culturally informed tool which allows

the provider to understand the client’s perspective and worldview and achieves

the goal of inviting in the client’s perspective and worldview in consideration

of assessment, diagnosis, and treatment.

Let’s now apply Hays’

framework to the following vignette. As you read through the case, consider

what aspects of the client’s identity are most salient in presentation of

symptoms.

Phil is a 67-year-old heterosexual, self-identified Christian,

Caucasian, married male. He states that his doctor suggested he seek therapy

after complaints of headaches and stomach pains that had no known medical

cause. He recently retired and lives in an urban city with his wife. They have

two children and three grandchildren.

During the intake, Phil indicated that he worries all the time, and

about “everything under the sun.” For example, he reports equal worry about his

wife who is undergoing treatment for breast cancer and whether he returned his

book to the library. He recognizes that his wife is more important than a book

and is bothered that both cause him similar levels of worry. According to

Phil, he is unable to control his worrying. Accompanying this excessive and uncontrollable

worry are difficulty falling asleep, impatience with others, difficulty

remembering things, and significant back and muscle tension.

Phil states that he has had a lifelong problem with worry, recalling

that his mother called him a “worry wart” as a kid. He reports that he was a

good kid in school who made mostly all As and Bs. He graduated from college

with a business degree and has worked as an accountant most of his life. He

recently retired and has spent most of his time caring for his ill wife. His

worrying does wax and wane, and it worsened when his wife was recently

diagnosed with breast cancer.

Consider that you are

employed at a clinic that uses CBT for anxiety treatment protocol. Phil is

initially reluctant to engage in treatment as his experience of his anxiety is

physiological and he is unsure of how “talking” about his problems will provide

relief. In the initial sessions, you assign homework consistent with your

treatment model that Phil does not complete. He is very apologetic and always

assures you he will return with his homework done the following week.

Using Pamela Hays

ADDRESSing model what cultural factors are relevant for this case? What

adaptations if any might be needed to increase engagement and participation in

treatment? How might this differ if you were using a different treatment model?

Some of the variables

that are important to consider are Phil’s age, status as a recent retiree,

cultural norms, and ideas about being a husband, father, and grandfather and

how his age and recent retirement affect his role as a father and husband. In

what way might his anxiety increase as a result of change in his status in

these roles?

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a term

developed in 1989 by the legal and race scholar Kimberle Crenshaw to explain

marginalization and oppression. She stated, “Black women are sometimes

excluded from feminist theory and antiracist policy discourse because both are

predicated on a discrete set of experiences that often does not accurately

reflect the interaction of race and gender… Because the intersectional

experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does

not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the

particular manner in which Black women are subordinated” (p. 140).

The concept of

intersectionality has been adopted by multiple professions including the American

Psychological Association (2017): social identities are interrelated,

interwoven, overlapping, and multi-layered. Consideration of privilege and

oppression based on social hierarchy addresses societal inequities. Identities

are not binary – for example, race – even within racial identity groups, skin color

can be associated with power or status. Or for immigration, assimilation may be

a significant variable that is associated with different levels of status

depending on the context.

Identities

- Gender

- Sexual orientation

- Gender identity

- Race

- Ethnicity

- Culture

- Language

- Language of origin

- Country and region of origin

- Immigration, immigration status,

citizenship

- Generation

- Acculturation

- Age

- Socioeconomic status

- Religion

- Spirituality

- Disability or Ableness

- Urban vs. rural/remote

- Body size

- Military experience

- Global, transnational

- Privilege / role of power

- Other factors including worldview

Consider your own identities,

intersections, and impacts with a particular client. Do they vary? Are certain

identities more prominent with a different client? How does that impact

assessment, diagnosis, case conceptualization, therapy? Then consider which of

your identities are associated with power and privilege? Which with oppression

and marginalization?

Then turn to consideration of

your client’s identities. Within a family constellation there may be significant

diversity in identities depending on the multiple aspects of identity

previously alluded to.

How different will therapy be

with a client who shares two or more identities with you versus one who shares

none? Are some of these implicit or explicitly discussed? Think of examples in

your current experience or during training.

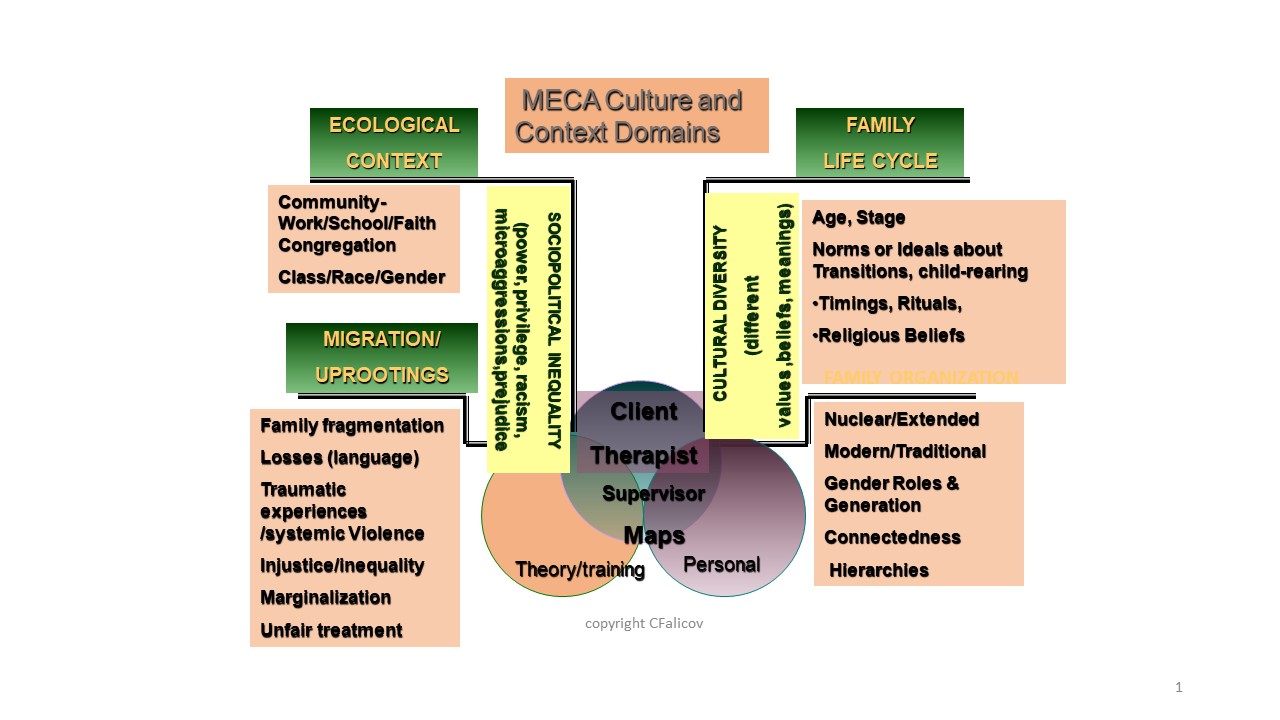

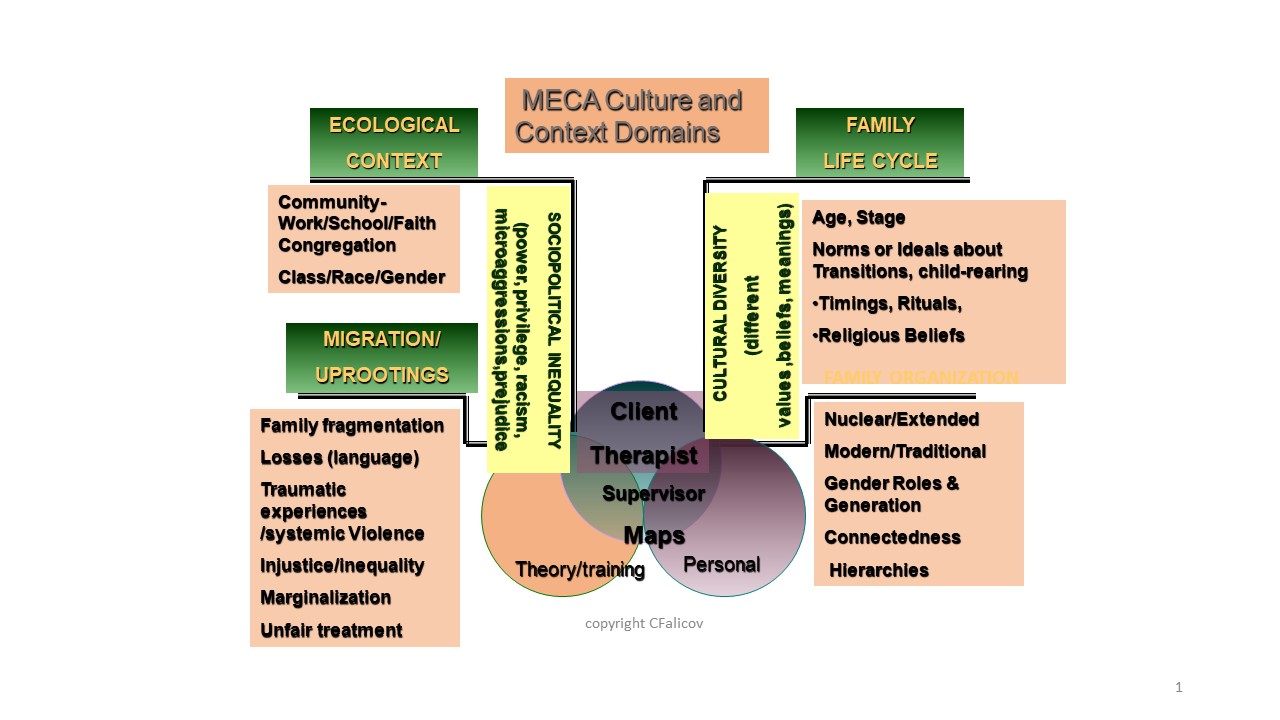

Falicov’s MECA Theory

A different framework

developed by Celia Falicov, is also useful in approaching intersectionality and

incorporating multiple aspects of diversity into practice. First, Celia

Falicov’s Multidimensional Ecosystemic

Comparative Approach (MECA) (Falicov, 2014; 2017) provides a framework

(Figure 1) that should not be your sole focus, but presents factors that are

essential to understand as part of an individual’s ecological niche, how they

fit in society. We are all multicultural beings and not subsumed under a

particular label or identity but by the intersections of those. These include

universals, particulars, or idiosyncratic histories, culture-specific aspects

(ethnic values, religious rituals), and each person’s ecological niche or

intersectional cultural identifiers. Note that the culture of each participant – client,

supervisee, and supervisor – are all included and essential in the cultural map

and formulation. Contextually, values, beliefs and meanings are not inferred

but are considered in the frame of culture of the clinician and the

relationship of those to the client/family.

Note that for Falicov,