Learning Objectives

This is a beginning to intermediate course. Upon completion of this course,

mental health professionals will be able to:

- Describe how to apply the concepts of privacy, confidentiality, and privilege to mental

health records.

- Discuss which situations trigger legal waivers to break confidentiality.

- List the essential requirements governing release of records to third parties.

- Explain how current technologies require policies that differ from those based on paper documents.

The materials in this course are based on current published ethical standards and the most accurate information available to the authors at the time of writing. Many ethical challenges arise on the basis of highly variable and unpredictable contextual factors. This course material will equip clinicians to have a basic understanding of core ethical principles and standards related to the topics discussed and to ethical decision-making generally, but cannot cover every possible circumstance. When in doubt, we advise consultation with knowledgeable colleagues and/or professional association ethics committees. Most of our cases use contrived names in an effort at humor and to make them more memorable. We intend no disrespect to any patient or clinician. When one of our cases is in the public domain, we use the actual person’s name and cite the public source.

Course Outline

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Secrets of Dead People

Espionage

Sensitivity to Technological Developments

A PROBLEM OF DEFINITIONS

Privacy

Confidentiality

Privilege

LIMITATIONS AND EXCEPTIONS

Statutory Obligations

Malpractice and Waivers

The Duty to Warn or Protect Third Parties from Harm

HIV and AIDS

Imminent Danger and Confidentiality

ACCESS TO RECORDS AND PERSONAL HEALTH INFORMATION

Consent for the Release of Records

Client Access to Records

Access by Family Members

Court Access to Records

Computer Records and Cyber-confidentiality

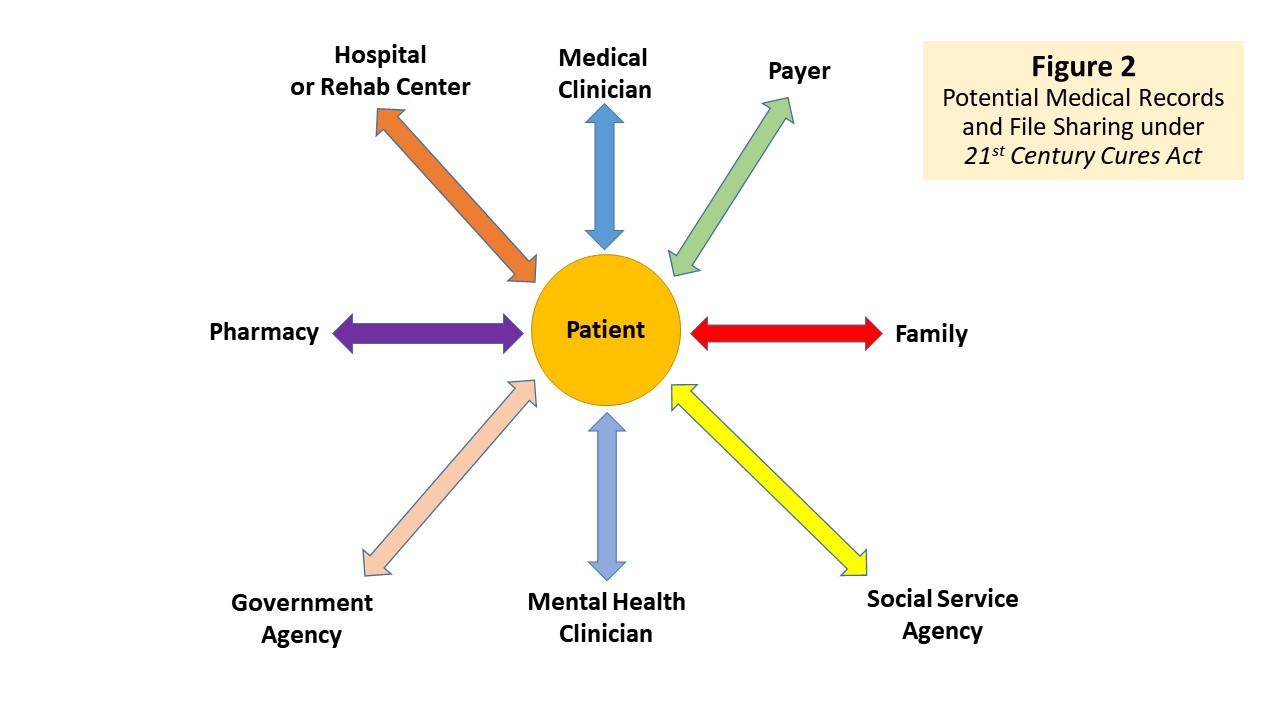

Mental Health Records and the 21st Century Cures Act

Third-Party Access: Insurers and Managed Care

TAKING ADVANTAGE OF CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION

RECORD CONTENT RETENTION AND DISPOSITION

Content of Records

Record Retention

Disposition

Introduction: What do you know, and who will you tell?

The confidential relationship between

mental health professionals and their clients has long stood as a cornerstone

of the helping relationship. The trust conveyed through assurance of confidentiality

seems so critical that some have gone so far as to argue that therapy might

lack all effectiveness without it (Epstein, Steingarten, Weinstein, & Nashel,

1977). In the words of Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, citing the amicus briefs of the American

Psychological and Psychiatric Associations:

Effective psychotherapy…depends

upon an atmosphere of confidence and trust in which the patient is willing to

make a frank and complete disclosure of facts, emotions, memories, and fears.

Because of the sensitive nature of the problems for which individuals consult

psychotherapists, disclosure of confidential communications made during counseling

sessions may cause embarrassment or disgrace. For this reason, the mere possibility

of disclosure may impede development of the confidential relationship necessary

for successful treatment. (Jaffe v Redmond, 1996)

The changing nature of societal demands and information technologies have led many to express concerns about the traditional meaning of confidentiality in mental health practice and even whether true privacy exists any more.

Material in this online course has been adapted from Ethics in Psychology

and the Mental Health Professions: Standards and Cases (4th Edition), published by Oxford

University Press, and additional new material has been added. © 2016 Gerald P. Koocher and Patricia Keith-Spiegel, all

rights reserved. Please note that all case material has been drawn from public

records or the experience of the authors. Public cases are documented with

media or legal citations. Other cases use intentionally humorous names and

disguised details to protect the privacy of those involved.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

American history provides ample public examples of how breaches in confidentiality

of mental health data have had major implications for both the clients and society.

Thomas Eagleton, a United States Senator from Missouri, was dropped as George

McGovern's vice presidential running mate in 1968 when it was disclosed that

he had previously been hospitalized for the treatment of depression (Post, 2004).

Dr. Lewis J. Fielding, better known as “Daniel Ellsberg's psychiatrist,” certainly

did not suspect that the break-in at his office by F.B.I. agents on September

3, 1971, might ultimately lead to the conviction of several high officials in

the Nixon White House and contribute to the only resignation of an American

president (Morganthau, Lindsay, Michael, & Givens, 1982; Stone, 2004). Disclosures

of confidential information received by therapists also played prominently in

the press during the well-publicized murder trials of the Menendez brothers

(Scott, 2005) and O. J. Simpson (Hunt, 1999). In the Menendez case, threats

made by one brother to the other’s psychotherapist, Dr. Jerome Oziel, contributed

to their conviction. In the Simpson case, a psychotherapist who had briefly

treated the late Nicole Simpson drew national attention when she felt the

need to “go public” shortly after the homicide, revealing content from the therapy

sessions. Subsequently, that same therapist drew disciplinary sanctions from

the California licensing board because of that confidentiality violation.

Secrets of Dead People

Should a mental health professional’s duty of confidentiality end

when a client dies? Consider the following actual cases.

Case 1:

After the deaths of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman (see: Hunt, 1999)

Susan J. Forward, a clinical social worker who had held two sessions with

Ms. Simpson in 1992, made unsolicited disclosures regarding her deceased former

client. Ms. Forward commented in public that Ms. Simpson had allegedly reported

experiencing abuse at the hands of O. J. Simpson.

The California Board of Behavioral Science Examiners subsequently

barred Ms. Forward from seeing patients for 90 days and placed her on three

years’ probation. In announcing the decision Deputy Attorney General, Anne

L. Mendoza, who represented the board, commented, "Therapy is based on privacy

and secrecy, and a breach of confidentiality destroys the therapeutic relationship"

(Associated Press, 1995). Ms. Mendoza also noted that Ms. Forward had falsely

represented herself as a psychologist in television interviews. Ms. Forward

later asserted that she had not violated patient confidentiality because the

patient was dead, but had agreed not to appeal the board's decision in order

to avoid a costly legal fight.

Case 2:

On July 20, 1993, Vincent Walker Foster, Jr. was found dead in Fort Marcy

Park, near Virginia’s George Washington Parkway. At the time, Mr. Foster served

as a deputy White House counsel during President Clinton’s first term. He

had also been a law partner and personal acquaintance of Hillary Clinton.

Foster had struggled with depression and had a prescription for Trazodone,

authorized by his physician over the telephone just a few days earlier. His

body was found with a gun in one hand, and gunshot residue on that hand. An

autopsy determined that he died as the result of a shot in the mouth. A draft

of a resignation letter, torn into 27 pieces, lay in his briefcase. Part of

the note read, "I was not meant for the job or the spotlight of public

life in Washington. Here ruining people is considered sport" (Apple,

1993). Following investigations conducted by the United States Park Police,

the United States Congress, and Independent Counsels Robert B. Fiske and Kenneth

Starr, his death was ruled a suicide.

Shortly before his death, Mr. Foster had met with James Hamilton, his personal

attorney. Kenneth D. Starr, the Special Prosecutor investigating the Clinton

Administration, sought grand jury testimony from Foster’s lawyer. Foster’s family

refused to waive the deceased man’s legal privilege and Hamilton declined to

testify. The case quickly reached the Supreme Court, which deemed communications

between a client and a lawyer protected by attorney-client privilege even after

the client's death by a 6 to 3 vote. The majority opinion written by Chief Justice Rehnquist

noted that, “A great body of case law and weighty reasons support the position

that attorney-client privilege survives a client's death, even in connection

with criminal cases” (Swidler & Berlin and James Hamilton v. United States,

1998).

Case 3:

Author Diane Middlebrook set out to write a biography of then-deceased

Pulitzer Prize winning poet Anne Sexton with the permission of Sexton’s family

(Middlebrook, 1991). Martin Orne, M.D., Ph.D. served as Sexton’s psychotherapist

for the last years of her life. At Sexton’s request, Dr. Orne had tape recorded

the sessions so that Sexton, who had a history of alcohol abuse and memory

problems, could listen to them as she wished. Dr. Orne had not destroyed the

tapes and Ms. Middlebrook sought access to them to assist in her writing.

Linda Gray Sexton, the poet’s daughter and executrix of her literary estate,

granted permission, and Dr. Orne released the tapes as requested.

Dr. Orne’s release of the audiotapes caused considerable debate within the profession despite authorized release (Burke, 1995; Chodoff, 1992; Goldstein, 1992; Joseph, 1992; Rosenbaum, 1994). Unlike the Simpson and Foster cases, the Sexton case involved release of the audio records approved by a family member with full legal authority to grant permission. In some circumstances, courts may order opening a deceased person’s mental health records. Examples might include assisting an inquest seeking to rule on suicide as a cause of death or to determine the competence of a person to make a will should heirs dispute the document at probate. Cases 1 through 3 involved situations with clear legal authority; however, often mental health professionals will encounter circumstances in which the solution must rely on ethical principles as well as legal standards (Werth, Burke, & Bardash, 2002). For example, in some situations, the legal standard may allow disclosure, whereas clinical issues or the mental health of others may lead to an ethical decision in favor of nondisclosure.

Consider the following case:

Case 4:

Sam Saddest had cystic fibrosis with severe lung disease. In his mid-20s, Sam no longer had enough energy or financial resources to live independently, although his illness did not seem likely to prove fatal for at least two to three more years. His medical condition forced him to give up his own apartment and move in with his divorced father, who had plans to marry again, this time a woman with two children, none of whom Sam liked. With his therapist, Michael Muted, M.D., Sam discussed his sadness about his mortality, unhappiness about the impending living situation, and resulting thoughts about suicide. Despite excellent clinical care and suicide precautions, Sam killed himself without reporting increased suicidal ideation or giving a hint of warning to anyone. Sam’s father subsequently met with Dr. Muted in an effort to understand Sam’s death. Dr. Muted discussed Sam’s frustration with his terminal illness and inability to continue living independently, knowing that the father understood those issues well. However, Dr. Muted never disclosed Sam’s distress about the father’s planned remarriage or unhappiness with the soon-to-be blended family situation.

In this case, the therapist made efforts to assist the survivor of a family member’s suicide to cope. The father readily understood and had known about these issues through discussions with his son over the prior months. Sam had not discussed his feelings about his father’s remarriage openly as he did not want to hurt his father or stir up a sense of guilt. Dr. Muted’s decision to keep Sam’s confidence post death respected Sam’s preferences and avoided causing incremental distress to the surviving family members. The key to resolving such issues will involve remembering that clients do have some rights to confidentiality that survive them, and giving due consideration to the welfare of the survivors.

Espionage

More recently, following the attack on the World Trade Center, the Foreign

Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) and Section 215 of the USA Patriot Act

(i.e., officially known as "Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing

Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001")

have made it clear that the illegal break-in to Dr. Fielding's office in 1971

could conceivably become a routinely legal practice just three decades later

(Morganthau, Lindsay, Michael, & Givens, 1982; Stone, 2004). Provisions of the Act covering roving wiretaps, searches of business records, and surveillance of so-called “lone wolves” (i.e., individuals suspected of posing terrorist threats, although unaffiliated with terrorist groups) now extend until 2015 (Mascaro, 2011). Although we

know of no instance in which a mental health professional has faced secret searches

of client records based on national security, the well documented case of Theresa

Squillacote illustrates the potential intrusion of security agencies into the

realm of psychotherapy.

Case 5:

Theresa Marie Squillacote, a.k.a. Tina, a.k.a. Mary Teresa

Miller, a.k.a. The Swan, a.k.a. Margaret, a.k.a. Margit, a.k.a. Lisa Martin, and

her husband, Kurt Stand were convicted of espionage. Squillacote earned a

law degree and worked for the Department of Defense in a position requiring

security clearance. In 1996, the FBI obtained a warrant to conduct clandestine

electronic surveillance, including the monitoring of all conversations in

Squillacote's home, calls made to and from the home, and Squillacote's office.

Based on the monitored conversations, including Squillacote's conversations

with her psychotherapists, a Behavioral Analysis Program team (BAP) at the

FBI, prepared a report of her personality for use in furthering the investigation.

The BAP report noted that she suffered from depression, took anti-depressant

medications, and had "a cluster of personality characteristics often

loosely referred to as 'emotional and dramatic.'" The BAP team recommended

taking advantage of Squillacote's "emotional vulnerability," by

describing the type of person with whom she might develop a relationship and

pass on classified materials. Ultimately, she did transmit national defense

secrets to a government officer who posed as a foreign agent and used strategies

provided by the BAP team (United States v. Squillacote, 2000).

Consider the possibilities with today’s “smart phone” technologies. Potential lone-wolf terror suspects can theoretically now be tracked and monitored while visiting their psychotherapists’ offices with devices that capture the therapist-client interaction in real time!

Sensitivity to Technological Developments

We cannot ignore the special sensitivity of information gleaned by both clinicians

and behavioral scientists in their work, whether assessment, psychotherapy,

consultation, or research. Unfortunately, the complexity of the issues related

to the general theme of confidentiality often defies easy analysis. Bersoff writes

of confidentiality that, “no ethical duty [is] more misunderstood or honored

by its breach rather than by its fulfillment” (1995, p. 143). Modern telecommunications

and computers have substantially complicated matters. Massive electronic databases

of sensitive personal information can easily be created, searched, cross tabulated,

combined with tracking signals, and transmitted around the world at the speed of light. Even prior to the Internet

and the World Wide Web, mental health professionals expressed concerns about

the threats posed to individual privacy and confidentiality by computerized

data systems (Sawyer & Schechter, 1968).

Lax practices with fax or other electronic transmissions provide but one example of ways that technology

can lead to unintended or inadvertent betrayal of confidentiality:

Case 6:

Edgar Fudd, Ph.D., decided to send the third billing notice to a slow-to-pay

client to the fax machine in the client's office. However, the client was not in the

office that day. The bill labeled psychological services rendered with the

client’s name and “Third Notice--OVERDUE!!” handwritten with a

wide marker sat in the open-access mail pickup tray of the busy office

all day.

Case 7:

Sentin Haste, M.S.W., was in a hurry to turn in her billing slip and medical record notations at the hospital where she worked. The usual practice involved slipping the forms into a scanning system that e-mailed copies to the central record-processing office. As she quickly punched in the e-mail address, an auto-completion function entered the address of her bridge club list server. Nearly 100 of her fellow players received electronic copies.

Fudd's behavior was obviously improper, and he should have known

better. Even if he was angry at the client for ignoring his bill, he should

have surmised that others in a place of business likely had access to the fax

machine. Obviously, no private or sensitive material should be sent via fax unless

it is known for sure that the recipient is the only one with access to it or

a telephone call verifies that the intended party is standing by the machine,

ready to retrieve it. In addition, Fudd’s creditor message sent to the client’s

workplace may violate debt collection laws.

Haste’s misstep illustrates the danger of transmitting confidential information in error. She hastily sent a message to the bridge club explaining the error and asking them to delete the prior message without reading it. To make matters worse, several of her fellow bridge club members “replied all,” saying “What an awful accident,” thereby calling even more attention to the error. Of course, she had no idea how many read the confidential patient information or deleted it. Ms. Haste had to report the error to her institution, which in turn had to notify the patient of the record breach under federal law.

In another case, scores of detailed, confidential medical records are reported to have been faxed to an accountant's office with a telephone number very similar to that of the intended recipient. Despite the accountant's numerous attempts to inform the sender so that the situation could be remedied, confidential records continued to arrive at her office (Stanley & Palosky, 1997).

Mental health professionals have both ethical and legal obligations to keep

records of various sorts (e.g., interactions with clients and research participants,

test scores, research data, and even patient account information) and must safeguard

these files. Increasingly, people seek all types of medical and psychological

information about others and about themselves. This leads to an entirely new

subset of problems on the matter of records: What is in them? Who should keep

them? How long should they be kept? Who has access? Is this a legal matter or

a professional standard? How do these policies have an impact on the ethical

principle of confidentiality? What about the rights of our students and research

subjects? We attempt to address all such matters in this course.

A PROBLEM OF DEFINITIONS

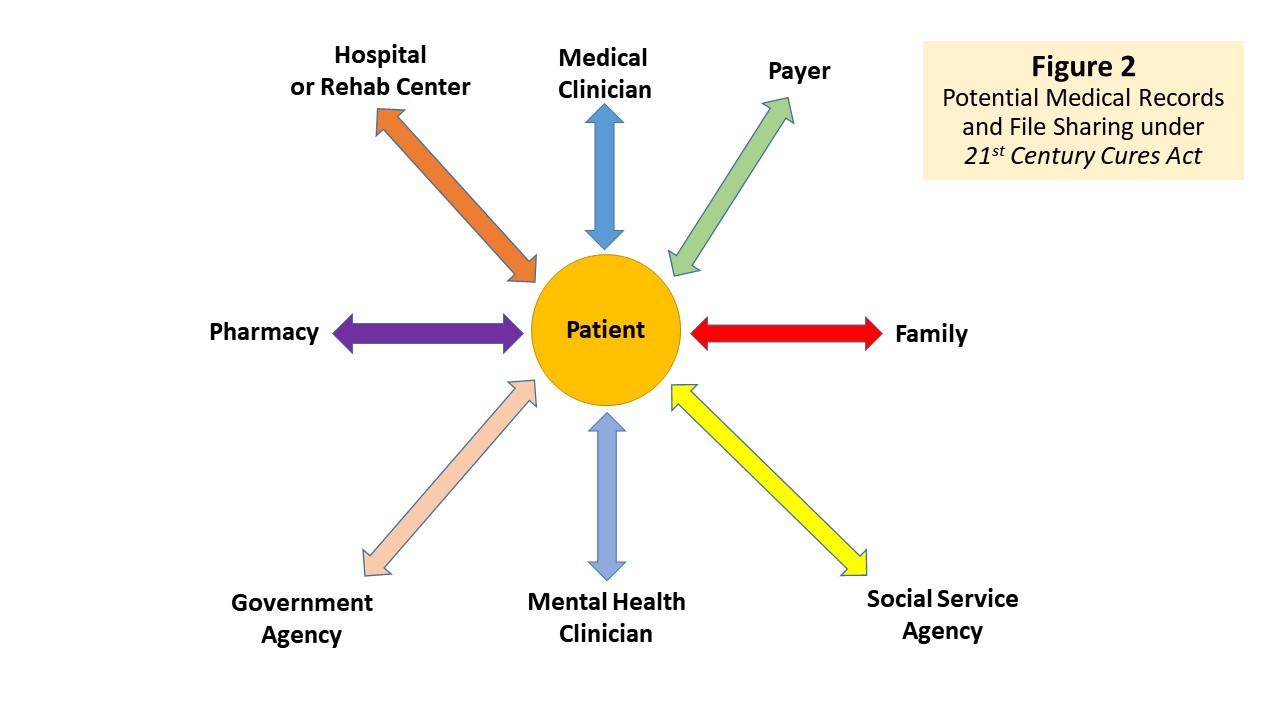

Figure 1

Illustration of Breadth of Protections

Confusion about three commonly used terms: privacy, confidentiality, and privilege,

often complicates discussions of ethical problems in this arena. Figure 1 attempts

to illustrate the breadth of coverage for each of the concepts (described below)

using a Venn diagram. At least part of the confusion flows from the fact that

in particular situations these terms may have narrow legal meanings quite distinct

from the broader traditional meanings attached by mental health practitioners. Many

difficulties link to a failure on the part of professionals to discriminate among

the different terms and meanings. Still other dilemmas stem from the fact

that legal obligations do not always align with ethical responsibilities.

Privacy

Although the word "privacy" does not occur in the United

States Constitution, some amendments (e.g., freedom of speech and to peaceably assemble, protection from unwarranted search and seizure, and to be “secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects) provides safeguards against unbridled government intrusion, as expanded in Justice Brandeis’s oft-cited dissent in Olmstead et al. v. U.S. (1928):

The makers of our Constitution undertook to secure conditions favorable to the pursuit of happiness. They recognized the significance of man's spiritual nature, of his feelings, and of his intellect. They knew that only a part of the pain, pleasure and satisfactions of life are to be found in material things. They sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations. They conferred to individuals, as against the Government, the right to be let alone – the most comprehensive of rights, and the right most valued by civilized men.

Privacy involves the basic entitlement of people to decide how much of their property,

thoughts, feelings, or personal data to share with others. In this sense, privacy

seems essential to ensure human dignity and freedom of self-determination.

In Figure 1, the breadth of the concept is represented in the largest circle.

The concepts of both confidentiality and privilege grow out of

the broader concept of an individual's right to privacy. Concern about electronic

surveillance, the use of lie detectors, and a variety of other observational

or data-gathering activities fall under the heading of privacy issues.

The issues involved in public policy decisions regarding the violation of privacy

rights parallel concerns expressed by therapists regarding confidentiality violations

(Smith-Bell & Winslade, 1994). In general, mental health professionals'

privacy rights may fall subject to violation when their behavior seriously violates

the norms of society or somehow endangers others. An example would be the issuance

of a search warrant based on "probable cause” that a crime has taken place

or may soon occur. We discuss these principles from the psychological perspective

in greater detail in the pages that follow. However, mental health professionals

must also give consideration to the concept of privacy as a basic human right

due all people and not simply limited to their clients.

We readily acknowledge that some societies, particularly in Africa and Asia,

do not place the same value on individual rights as opposed to community rights, as

do most Western societies. Therapists must remain sensitive and respectful to

cultural differences in this regard. At the same time, we must also obey the

laws of the jurisdictions in which we practice. At times, this may create tensions

that require helping people from other cultures to understand applicable laws

and regulations that apply in the immediate circumstances at hand.

Case 8:

Shana Shalom, an orthodox Jewish émigré from Israel sought counseling

from Hebrew-speaking therapist Tanya Talmud,

M.S.W. regarding her unhappy marriage. Ms. Shalom later complained to the state licensing board that Ms. Talmud

discussed matters she had disclosed in therapy with the family rabbi without

her knowledge or consent. The rabbi, in turn, communicated some of the content

to Ms. Shalom’s spouse. Ms. Talmud replied to the licensing board that in

Israel’s orthodox Jewish communities, soliciting aid from a couple’s rabbi

often proves a useful way to address marital problems.

The licensing board censured Ms. Talmud, reminding her that she

treated Ms. Shalom in her capacity as a licensed social worker in the United

States, not Israel. In addition, basic ethical principles of autonomy and human

dignity entitled Ms. Shalom to have a voice in any decision about disclosing

material offered in confidence.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality refers to a general standard of professional conduct that

obliges a professional not to discuss information about a client with anyone.

In Figure 1, the breadth of the concept is represented in the middle-sized inner

circle – narrower than the concept of privacy, but more broad than privilege.

Confidentiality may also originate in statutes (i.e., laws enacted by legislatures),

administrative law (i.e., regulations promulgated to implement legislation),

or case law (i.e., interpretations of laws by courts). But, when cited as an

ethical principle, confidentiality implies an explicit contract or promise not

to reveal anything about a client except under certain circumstances agreed

to by both parties. Although the roots of the concept are in professional ethics

rather than in law, the nature of the relationship between client and therapist

does have substantial legal recognition (see, for example, jaffee-redmond.org).

One can imagine, for example, that clients who believe their confidences have

been violated could sue their psychotherapists in a civil action for breach

of confidentiality and possibly seek criminal penalties if available under state

law. For example, a New York appeals court ruled that a patient may bring a

tort action against a psychiatrist who allegedly disclosed confidential information

to the patient's spouse, allowing him to seek damages for mental distress, loss

of employment, and the deterioration of his marriage (Disclosure of Confidential

Information, 1982; Fisher, 2013; MacDonald v. Clinger, 1982).

The degree to which one should, if ever, violate a client's confidentiality

remains a matter of some historical controversy (see, for example, Siegel, 1979),

despite uniform agreement on one point: all clients have a right to know the

limits on confidentiality in a professional relationship from the outset. The

initial interview with any client (individual or organizational) should include

a direct and candid discussion of limits that may exist with respect to any

confidences communicated in the relationship (American Psychological Association [APA]: 4.02; American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy [AAMFT]: 1.13; American Counseling Association [ACA]: B.1.d; National Association of Social Workers [NASW]: 1.07). State and federal laws require

providing such information in both health care (e.g., Public Law 104-191, Health

Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996; a/k/a: HIPAA) and forensic

contexts (e.g., Commonwealth v. Lamb, 1974; Barefoot v. Estelle, 1983). Not only will failure to

provide such information early constitute unethical behavior and possibly

illegal behavior in health care settings, but such omissions may also lead to clinical

problems later. In some contexts conveying such information orally may suffice,

but documenting the conversation becomes critical. Health care providers will

need to provide a formal written HIPAA notice, and those who provide non-health

related services may want to do likewise or possibly provide “new client information”

in a pamphlet or other written statement. Every therapist should give sufficient

thought to this matter and formulate a policy for his or her practice that complies

with applicable law, ethical standards, and personal conviction, integrated

as meaningfully as possible given the legal precedents and case examples discussed

in the following pages.

Privilege

The concepts of privilege and confidentiality often become confused, and the

distinction between them has critical implications for understanding a variety

of ethical problems. The concept of privilege (or privileged communication)

describes certain specific types of relationships that enjoy protection from

disclosure in legal proceedings. In Figure 1, the breadth of this very narrow

concept is represented in the smallest circle. Designation of privilege originates

in statute or case law and belongs to the client in the relationship. Normal

court rules provide that anything relative and material to the issue at hand

can and should be admitted as evidence. When privilege exists, however, the

client has a degree of protection against having the covered communications

revealed without explicit permission. If the client waives this privilege, the

clinician must testify on the nature and specifics of the material discussed.

The client cannot usually permit a selective or partial waiver. In most courts,

once a waiver is given, it covers all of the relevant privileged material.

Traditionally, such privilege extended to attorney-client, husband-wife,

physician-patient, and certain clergy relationships. Some jurisdictions

now extend privilege to the relationships between clients and mental health

practitioners, but the actual laws vary widely, and each mental

health professional has an ethical obligation to learn the statutes or case

law in force for her or his practice jurisdiction. Prior to 1996 many states

addressed the primary mental health professions (i.e., psychologists, psychiatrists,

and social workers) while omitting mention of psychiatric nurses, counselors,

or generic psychotherapists. (DeKraai & Sales, 1982). The same authors also

noted that no federally created privileges existed for any mental health profession

and that the federal courts generally looked to applicable state laws. All that

changed in 1996 when the U.S. Supreme Court took up the issue based, in part,

on conflicting rulings in different federal appellate court districts (Jaffe

v. Redmond, 1996).

Case 9:

Mary Lu Redmond was a police officer in Hoffman Estates, Illinois, a suburb

of Chicago. On June 27, 1991, while responding to a “fight in progress” call,

she fired her weapon and killed Ricky Allen, Sr. as he pursued, rapidly gained

ground on, and stood poised to stab another man with a butcher knife. After

the shooting, Officer Redmond sought counseling from a licensed clinical social

worker. Later, Carrie Jaffe, acting as administrator of Mr. Allen's estate,

sued Redmond, citing alleged U.S. civil rights statutes and Illinois tort

law. Jaffe wanted access to the social worker's notes and sought to compel

the therapist to give oral testimony about the therapy. Redmond and her therapist,

Karen Beyer, a licensed clinical social worker refused. The trial judge instructed

the jury that refusing to provide such information could be held against Officer

Redmond. The jury awarded $545,000 damages based on both the federal civil

rights and state laws.

On June 13, 1996, the Supreme Court overturned the lower court

decision, upholding the existence of a privilege under Federal Rules of Evidence

to patients of licensed psychotherapists by a vote of 7-2. In a decision

written by Justice John Paul Stevens, the Court noted that this privilege is

“rooted in the imperative need for confidence and trust,” and that “the mere

possibility of disclosure may impede development of the confidential relationship

necessary for successful treatment,” (Jaffe v. Redmond, 1996, 4492-4493).

Writing for himself and Chief Justice Renquist, Justice Scalia dissented, arguing

that psychotherapy should not be protected by judicially created privilege and

that social workers were not clearly experts in psychotherapy and did not warrant

such a privilege (Smith, 1996). Justice Scalia attempted to simplify the matter by noting: “Ask the average citizen: Would your mental health be more significantly impaired by preventing you from seeing a psychotherapist, or by preventing you from getting advice from your mom? I have little doubt what the answer would be. Yet there is no mother-child privilege.” (p. 22). Nonetheless, this case has set a new national

standard that affords privilege protections across jurisdictions, generally

implying that a Federal privilege extends to licensed mental health professionals.

LIMITATIONS AND EXCEPTIONS

Almost all of the statutes addressing confidentiality or providing

privileges expressly require licensing, certification, or registration of mental

health professionals under state law, although some states extend privilege

when the client reasonably believes the alleged therapist to be licensed (DeKraai

& Sales, 1982). Clients of students (including psychology interns, unlicensed

postdoctoral fellows, or supervisees) may not specifically have coverage under

privilege statutes. In some circumstances, trainees’ clients may have privilege

accorded to communication with a licensed supervisor, but state laws vary widely,

and practitioners should not take this coverage for granted. The oral arguments before the Supreme Court (oyez.org/cases/1990-1999/1995/1995_95_266) relied on the reasonable expectation of the client on such protection, but left unclear whether the clients of unlicensed therapists are protected.

Some jurisdictions permit a judge's discretion to overrule privilege between

therapist and client on determination that the interests of justice outweigh

the interests of confidentiality. Some jurisdictions limit privilege exclusively

to civil actions, whereas others may include criminal proceedings, except in

homicide cases. In many circumstances, designated practitioners have a legally

mandated obligation to breach confidentiality and report certain information

to authorities. Just as some physicians must under some state laws report gunshot

wounds or certain infectious diseases, mental health practitioners may have

an obligation to report certain cases, such as those involving child abuse,

to state authorities. These restrictions could certainly affect a therapeutic

relationship adversely, but the client has a right to know any limitations in

advance, and the clinician has the responsibility both to know the relevant

facts and to inform the client as indicated.

Other circumstances, such as a suit alleging malpractice, may constitute a

waiver of privilege and confidentiality. In some circumstances, a client may

waive some confidentiality or privilege rights without fully realizing the extent

of potential risk. In certain dramatic circumstances, a therapist may also face

the dilemma of violating a confidence to prevent some imminent harm or danger

from occurring. These matters are not without controversy, but it is important

for mental health professionals to be aware of the issues and to think prospectively

about how one ought to handle such problems.

When law and ethical standards diverge (e.g., when a confidential communication

does not qualify as privileged in the eyes of the law), the situation becomes

extremely complex. One cannot, however, ethically fault a therapist for divulging

confidential material if ordered to do so by a court of competent authority.

On the other hand, one might reasonably question the appropriateness of violating

the law if one believes that doing so has become necessary to behave ethically.

Consider, for example, the clinician required by state law or court order to

disclose some information learned about a client during the course of a professional

relationship. If the practitioner claims that the law and ethical principles

conflict, then by definition the ethical principles in question would seem illegal.

The therapist may choose civil disobedience as one course of action, but does

so at his or her own peril in terms of the legal consequences. The American Psychological Association ethics code does mandate that psychologists actively attempt to resolve such conflicts.

Students of ethical philosophy will immediately recognize a modern psychological

version of the controversy developed in the writings of Immanuel Kant and John

Stuart Mill. Which matters more: the intention of the actor or solely the final

outcome of the behavior? For example, if competent therapists, intending to

help their clients, initiate interventions that cause unanticipated harm, have

they behaved ethically (because they had good intentions) or unethically (because

harm resulted)? We do not have the answer. Each situation presents

different fact patterns, but the most appropriate approach to evaluating a case

would involve considering the potential impact of each alternative course of

action and choosing the most reasonable one. Perhaps the best guidepost we can

offer involves a kind of balancing test in which the clinician attempts to weigh

the relative risks and vulnerabilities of the parties involved. Several of the

cases discussed in this course highlight such difficult decisions.

Statutory Obligations

As noted above, in some circumstances the law specifically dictates

a duty to notify certain public authorities of information that might be acquired

in the context of a therapist-client relationship. The general rationale

on which such laws are predicated holds that certain individual rights must

give way to the greater good of society or to the rights of a more vulnerable

individual (e.g., in child abuse or child custody cases; see Kalichman, 1993).

Statutes in some states address the waiver of privilege in cases of clients

exposed to criminal activity either as the perpetrator, victim, or third party.

One might presume that violation of a confidence by obeying one's legal duty

to report such matters (in the states where such duties exists) could certainly

hinder the therapist-client relationship, yet the data on this point seem

mixed (DeKraai & Sales, 1982; Kalichman, Brosig, & Kalichman, 1994;

Nowell & Sprull, 1993; Woods & McNamara, 1980). Some commentators have

argued that the therapeutic relationship can survive a mandated breach in confidentiality

so long as a measure of trust is maintained (Brosig & Kalichman, 1992; Watson

& Levine, 1989). At times, state laws can be confusing and complicated.

Case 10:

Euthan Asia was full of remorse when he came to his initial appointment

with Oliver Oops, Ph.D. After asking and receiving assurance that their conversations

would be confidential, Mr. Asia disclosed that, two months earlier, he had

murdered his wife of 50 years out of compassion for her discomfort. Mrs. Asia

was 73 years old and suffered from advanced Alzheimer's disease. Mr. Asia

could not stand to see the woman he loved in such a state, so he gave his

wife sleeping pills and staged a bathtub drowning that resulted in a ruling

of accidental death by the medical examiner.

In some jurisdictions, Dr. Oops would be obligated to respect Mr. Asia's confidentiality

because those states do not mandate reporting of past felonies that do not involve

child abuse. If the conversation took place in Massachusetts, however, Dr. Oops

would be required by law to report Mr. Asia twice. First, Dr. Oops would have

to notify the Department of Elder Affairs that Mr. Asia had caused the death

of a person he was caring for over the age of 60. Next, he would be obligated

to report to another state agency that Mr. Asia had caused the death of a handicapped

person. Although every American state and Canadian province has mandatory

“child abuse” reporting laws (Kalichman, 1993), not all have statutes mandating

the reporting of abuse of so-called “dependent persons.” As a result, mental health professionals

have an affirmative ethical obligation to know all applicable exceptions for

the jurisdiction in which they practice, and to provide full information on these

limits to their clients at the outset of the professional relationship (APA

10: 4.02b).

Therapists worry about the potential obligation to disclose a client's stated

intent to commit a crime at some future date. Shah (1969) argued that, in most

cases, such disclosures of intent essentially constitute help-seeking behavior

rather than an actual intent to commit a crime. Siegel (1979) also argued that

interventions short of violating a confidence will invariably prove possible

and more desirable, although he acknowledged that one must obey any applicable

laws. No jurisdictions currently mandate mental health professionals to disclose

such information. The prime exception to treating statements of intent to commit

crimes confidentially involves the special context when particular clients pose

a danger to themselves or others; discussed in the following material as the “duty to warn or protect.”

Malpractice and Waivers

Although not all states have specifically enacted laws making malpractice actions

an exception to privilege, one must allow defendant therapists to defend themselves

by revealing otherwise confidential material about their work together. Likewise,

no licensing board or professional association ethics committee could investigate

a claim against a mental health practitioner unless the complainant waives any

duty of confidentiality that the therapist might owe. In such instances, the

waiver by the client of the therapist’s duty of confidentiality or any legal

privilege constitutes a prerequisite for full discussion of the case. While

some might fear that the threat to reveal an embarrassing confidence would deter

clients from reporting or seeking redress from offending therapists, procedural

steps can allay this concern. Ethics committees, for example, generally conduct

all proceedings in confidential sessions and may offer assurances of privacy

to complainants. In malpractice cases, judges can order spectators excluded from

the courtroom and place records related to sensitive testimony under seal from

the public’s view.

In some circumstances, a therapist may want to advise an otherwise willing

client not to waive privilege or confidentiality.

Case 11:

Barbara Bash, age 23, suffered a concussion in an automobile accident,

with resulting memory loss and a variety of neurological sequelae. Her condition

improved gradually, although she developed symptoms of depression and anxiety

as she worried about whether she would fully recover. She sought a consultation

from Martha Muzzle, Ph.D., to assess her cognitive and emotional state, subsequently

entering psychotherapy with Dr. Muzzle to deal with her emotional symptoms.

During the course of her treatment Ms. Bash informed Dr. Muzzle that she had

previously sought psychotherapy at age 18 to assist her in overcoming anxiety

and depression linked to a variety of family problems. Some 10 months after

the accident, Bash had continued treatment and made much progress. A lawsuit

remains pending against the other driver in the accident, and Bash's attorney

wonders whether to call Dr. Muzzle as an expert witness at the trial to document

the emotional pain Ms. Bash suffered, thus securing a better financial settlement.

If consulted, the therapist should remind Ms. Bash's attorney and inform Ms.

Bash that, if called to testify on Ms. Bash's behalf, she would have to waive

her privilege rights. Under cross examination, the therapist might have to respond

to questions about preexisting emotional problems, prior treatment, and a variety

of other personal matters that Ms. Bash might prefer not to have brought out

in court. In this case, the legal strategy involved documenting Bash's damages,

with the intent of forcing an out-of-court settlement, but the client

ought to know the risks of disclosure should her attorney call the therapist

as a witness.

Employers, schools, clinics, or other agencies may also apply pressure for

clients to sign waivers of privilege or confidentiality. Often the client may

actually not wish to sign the form, but may feel obligated to comply with the

wishes of an authority figure or feel fearful that requested help would otherwise

be turned down (Rosen, 1977). If a mental health professional has doubts about

the wisdom or validity of a client's waiver in such circumstances, the best

course of action would call for consulting with the client about any reservations

prior to supplying the requested information.

The Duty to Warn or Protect Third Parties from Harm

No complete discussion of confidentiality in the mental health

arena can take place without reference to the Tarasoff case (Tarasoff v.

Board of Regents of the University of California, 1976) and a family of

so-called progeny cases that have followed in its wake (Quattrocchi & Schopp, 2005; VandeCreek & Knapp, 2001; Werth, Welfel, & Benjamin, 2009). Detailed historical analyses of the legal

case have evolved in the literature (Stone, 1976; Everstine, Everstine, Heymann,

et al, 1980; and Quattrocchi & Schopp, 2005), but a brief summary follows

for those unfamiliar with the facts.

Case 12:

In the fall of 1969, Prosenjit Poddar, a citizen of India and naval architecture

student at the University of California's Berkeley campus, shot and stabbed

to death Tatiana Tarasoff, a young woman who had spurned his affections. Poddar

had sought psychotherapy from Dr. Moore, psychologist at the university's

student health facility, and Dr. Moore had concluded that Poddar posed a significant

danger. This conclusion stemmed from an assessment of Poddar's pathological

attachment to Tarasoff and evidence that he intended to purchase a gun. After

consultation with appropriate colleagues at the student health facility, Dr.

Moore notified police both orally and in writing that he feared Poddar posed

a danger to Tarasoff. He requested that the police take Poddar to a facility

for hospitalization and an evaluation under California's civil commitment statutes.

The police allegedly interrogated Poddar and found him rational. They concluded

that he did not really pose a danger and secured a promise that he would stay

away from Ms. Tarasoff. After his release by the police, Poddar understandably

never returned for further psychotherapy, and two months later stabbed Tarasoff

to death.

Subsequently, Ms. Tarasoff's parents sued the regents of the University of

California, the student health center staff members involved, and the police.

Both trial and appeals courts initially dismissed the complaint, holding that,

despite the tragedy, no legal basis for the claim existed under California law.

The Tarasoff family appealed to the Supreme Court of California, asserting that

the defendants had a duty to warn Ms. Tarasoff or her family of the danger,

and that they should have persisted to ultimately ensure his confinement. In

a 1974 ruling, the court held that the therapists, indeed, had a duty to warn

Ms. Tarasoff. When the defendants and several amici (i.e., organizations trying

to advise the court by filing amicus curiae, or “friend of the court,” briefs)

petitioned for a rehearing, the court took the unusual step of granting one.

In their second ruling (Tarasoff v. Board of Regents, 1976), the court

released the police from liability without explanation and more broadly formulated

the obligations of therapists, imposing a duty to use reasonable care to protect

third parties against dangers posed by a patient:

We shall explain that defendant therapists cannot escape liability merely because Tatiana herself was not their patient. When a therapist determines, or pursuant to the standards of his profession should determine, that his patient presents a serious danger of violence to another, he incurs an obligation to use reasonable care to protect the intended victim against such danger. The discharge of this duty may require the therapist to take one or more of various steps, depending upon the nature of the case. Thus it may call for him to warn the intended victim or others likely to apprise the victim of the danger, to notify the police, or to take whatever other steps are reasonably necessary under the circumstances (Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 1976).

Although the influence of the decision outside of California was not immediately

clear, the issue of whether mental health professionals must be police or protectors

or otherwise have a “duty to protect” rapidly became a national concern (see,

e.g., Bersoff, 1976; Leonard, 1977; Paul, 1977; VandeCreek and Knapp 2001; Quattrocchi

and Schopp 2005). A former president of the APA (Siegel, 1979) even argued that

if Poddar's psychologist had accepted the absolute and inviolate confidentiality

position, Poddar could have remained in psychotherapy and never harmed Tatiana

Tarasoff. Siegel believed the therapist “betrayed” his client asserting that,

if the psychologist had not considered Poddar “dangerous,” no liability for

“failure to warn” would have developed. It has even been argued that more lives could be lost due to overzealous reporting mandates (Shapiro & Smith, 2011). Clients who need therapy the most may not return to therapy, possibly placing themselves or others at increased risk. Some in need of therapy may avoid seeking it if they suspect their confidences could be disclosed. Those who do enter therapy may not express what they actually feel or intend to do (Ritter & Tanner, 2013). Such claims may have some validity; however, many therapists would support the need to protect the public welfare via direct

action. From both legal and ethical perspectives, a key test of responsibility

remains whether therapists knew or should have known (in a professional capacity)

of the client's dangerousness. No single ethically correct answer will apply

in all such cases, but the therapists must also consider their potential obligations.

Currently, most states expect therapists to take protective action when clients make specific threats as alluded to in the final opinion of the California Supreme Court:

We shall explain that defendant therapists cannot escape liability merely because Tatiana herself was not their patient. When a therapist determines, or pursuant to the standards of his profession should determine, that his patient presents a serious danger of violence to another, he incurs an obligation to use reasonable care to protect the intended victim against such danger. The discharge of this duty may require the therapist to take one or more of various steps, depending upon the nature of the case. Thus it may call for him to warn the intended victim or others likely to apprise the victim of the danger, to notify the police, or to take whatever other steps are reasonably necessary under the circumstances. (Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 1976)

Perhaps the ultimate irony of the Tarasoff case in terms of outcome

involves what happened to Mr. Poddar. His original conviction for second degree

murder was reversed because the judge had failed to give adequate instructions

to the jury concerning the defense of “diminished capacity” (People v. Poddar,

1974). He was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and confined to the Vacaville

medical facility in California and has since won release from confinement and

went back to India and claims to be happily married. (Stone, 1976).

A variety of decisions by courts outside California since Tarasoff

have dealt with the duty of therapists to warn or protect potential victims

of violence at the hands of their patients (Knapp & VandeCreek, 2000; Truscott,

1993; VandeCreek & Knapp, 1993, 2001; Weisner, 2006; Yufik, 2005). The cases

are both fascinating and troubling from the ethical standpoint.

The most recent scholarly colloquy on the issue began with Bersoff calling for an end to state statutes enacted after the Tarasoff decision that require therapists to warn the intended victim, police, and/or others when a patient voices serious threats of violence. He argued that such laws may actually interfere with therapy by deterring patients from revealing violent intent, because the therapists will have informed new patients of this exception to confidentiality. As an alternative to laws mandating that therapists disclose such threats, Bersoff suggests “discretion to disclose” (p. 461). He discusses this in terms of sensible options short of violating confidentiality (e.g., seeking consultation, recommending hospitalization, and extending therapy sessions to manage imminent threats). If these fail, the therapist could then opt to disclose (p. 466). Huey (2015) calls this a “Catch-22” situation, noting that any rules undercutting sacrosanct confidentiality create a situation in which the ethical necessity of informed consent has an unintended consequence in that truly open psychotherapy is preceded by informed consent that acts to preclude it. Huey notes that properly informed patients will choose not to reveal imminent suicidal intent, if they are unwilling to be hospitalized. Pedophiles who might consider seeking treatment would have to forgo it or face mandatory reporting, felony conviction, and lifetime public registration.

We have not disguised or synthesized examples in the next several cases, but

rather draw from public legal records that form a portion of the continually

growing case law on the duty to warn. The cases themselves do not necessarily

bespeak ethical misconduct. Rather, we cite them here to guide readers regarding

legal cases that interface with the general principle of confidentiality.

Case 13:

Dr. Shaw, a dentist, participated in a therapy group with Mr. and Mrs.

Moe Billian. Shaw became romantically involved with Mrs. Billian, only to

be discovered one morning at 2:00 A.M. in bed with her by Mr. Billian, who

had broken into Shaw's apartment. On finding his wife in bed nude with Dr.

Shaw, Mr. Billian shot at Shaw five times, but did not kill him.

Dr. Shaw sued the psychiatric team in charge of the group therapy program because

of the team's alleged negligence in not warning him that Mr. Billian's “unstable

and violent condition” presented a “foreseeable and immediate danger” to him

(Shaw v. Glickman, 1980). In this case, the Maryland courts held that,

although the therapists knew Mr. Billian carried a handgun, they could not necessarily

have inferred that Billian might have had a propensity to invoke the “old Solon

law” (i.e., a law stating that shooting the wife's lover could constitute justifiable

homicide) and may not even have known that Billian harbored any animosity toward

Dr. Shaw. The court also noted, however, that, even if the team had this information,

they would have violated Maryland law had they disclosed it.

Case 14:

Lee Morgenstein, age 15, had received psychotherapy from a New Jersey

psychiatrist, Dr. Milano, for 2 years. Morgenstein used illicit drugs and

discussed fantasies of using a knife to threaten people. He also told Dr.

Milano of sexual experiences and an emotional involvement with Kimberly McIntosch,

a neighbor 5 years his senior. Morgenstein frequently expressed anxiety and

jealousy about Ms. McIntosch’s dating other men, and he reported to Dr. Milano

that he once fired a BB gun at a car in which she was riding. One day, Morgenstein

stole a prescription blank from Dr. Milano, forged his signature, and attempted

to purchase 30 Seconal tablets. The pharmacist became suspicious and called

Dr. Milano, who advised the pharmacist to send the boy home. Morgenstein obtained

a gun after leaving the pharmacy and later that day shot Kimberly McIntosch

to death.

Dr. Milano had reportedly tried to reach his client by phone to talk about

the stolen prescription blank, but intervened too late to prevent the shooting.

Ms. McIntosch's father, a physician who had read about the Tarasoff decision,

and his wife ultimately filed a civil damage suit against Dr. Milano for the

wrongful death of their daughter, asserting that Milano should have warned Kimberly

McIntosch or taken reasonable steps to protect her.

Dr. Milano sought to dismiss the suit claiming that the Tarasoff principle

should not apply in New Jersey for four reasons. First, to do so would impose

an unworkable duty because the prediction of dangerousness is unreliable. Second,

violating the client's confidentiality would have interfered with effective

treatment. Third, assertion of the Tarasoff principle could deter therapists

from treating potentially violent patients. Finally, Milano claimed that all

of this might lead to an increase in unnecessary commitments to institutions.

The court rejected each of these arguments and denied the motion to dismiss

the case (McIntosch v. Milano, 1979). The court noted the duty to warn

as a valid concept under New Jersey law, and despite the fact that therapists

cannot be 100% accurate in predictions, they have the ability to weigh the relationships

of the parties. The court drew an analogy comparing the situation with warning

communities and individuals about carriers of a contagious disease, and stated

that confidentiality must yield to the greater welfare of the community, especially

in the case of imminent danger. Ultimately, a jury did not find Milano liable

for damages, but the Tarasoff principle had clearly moved East.

Case 15:

James, a juvenile offender, was incarcerated for 18 months at a county

facility. During the course of his confinement, James threatened that he would

probably “off some kid” (i.e., murder a child) in the neighborhood if released,

although he did not mention any particular individual. James obtained parole

and did indeed kill a child shortly thereafter.

In the litigation that resulted from this case (Thompson v. County of Alameda,

1980), the chief concern focused on whether the county had a duty to warn the

local police, neighborhood parents, or James' mother of his threats. While recognizing

the duty of the county to protect its citizens, the California Supreme Court

declined to extend the Tarasoff doctrine it had created a few years earlier

to this case, noting that doing so would prove impractical and negate rehabilitative

efforts by giving out general public warnings of nonspecific threats for each

person paroled. The court also deemed warning the custodial parent futile because

one would not expect her to provide constant supervision (Tarasoff duty…, 1980).

After many years of state court decisions clarifying the Tarasoff

doctrines, a 1991 Florida decision (Boynton v. Burglass, 1991) complicated

matters still further.

Case 16:

The Florida state appeals court declined to adopt a duty to warn and held

that a psychiatrist who knew or should have known that a patient presented

a threat of violence did not have a duty to warn the intended victim. The

case was brought against Dr. Burglass, a psychiatrist who had treated Lawrence

Blaylock. Mr. Blaylock shot and killed Wayne Boynton, and Boynton's parents

alleged that Burglass should have known about the danger to their son and

should have warned him. The trial court dismissed the case for failure to

state a cause of action. The appeals court declined to follow the Tarasoff

case, ruling that such a duty seemed, “neither reasonable nor workable and

is potentially fatal to effective patient-therapist relationships.”

The court cited the inexact nature of psychiatry and considered it virtually

impossible to foresee a patient's dangerousness. The court also noted a common

law rule that one person has no duty to control the conduct of another. Although

a “special circumstance” may create such an obligation in some cases, this

did not seem true in Blaylock's case because the treatment occurred as a voluntary

outpatient.

The bottom line for psychotherapists is this: consult a lawyer

familiar with the standards that apply in your particular jurisdiction. Such

consultation proved very helpful to the two practitioners who treated Billy

Gene Viviano:

Case 17:

In March 1985, a jury awarded Billy Gene Viviano $1 million for injuries

he had received at work. Much to Mr. Viviano's dismay, Judge Veronica Wicker

overturned the verdict and ordered a new trial. During the next several months,

Mr. Viviano became depressed and sought treatment from psychiatrist Dudley

Stewart and psychologist Charles Moan. During the course of his treatment,

Mr. Viviano voiced threats toward Judge Wicker and other people connected

with his lawsuit. Drs. Stewart and Moan informed the judge of these threats,

and Mr. Viviano was arrested, pleaded guilty to contempt of court, and agreed

to a voluntary psychiatric hospitalization. Viviano and his family sued the

two doctors for negligence, malpractice, and invasion of privacy, but the

jury found that the doctors had acted appropriately. Viviano appealed, but

lost again (In re Viviano, 1994).

In ruling for Drs. Stewart and Moan, the Louisiana Court of Appeals cited the

Tarasoff case, noted that Dr. Stewart repeatedly consulted an attorney prior

to disclosing the threats, and cited testimony by both doctors that Mr. Viviano's

threats had become increasingly intense to the point at which both believed

he would attempt to carry them out. After weighing these factors, the appellate

court reasoned the therapists had followed applicable standard of care in warning

third parties.

What should therapists do if a threat comes to their attention from a family

member, rather than the patient? More recently, the California courts have again

broken new ground in the confidentiality and duty to protect arena, again emphasizing

the need to obtain current legal advice when challenging cases come along, such as the

matter of Ewing v. Goldstein (2004).

Case 18:

David Goldstein, Ph.D., a licensed marriage and family therapist, had

treated Geno Colello, a former Los Angeles police officer, for three years.

Treatment focused on work-related injuries and the breakup of Colello’s seventeen-year relationship with a woman named Diana Williams, who had begun dating

Keith Ewing. Dr. Goldstein talked to Mr. Colello by telephone on June 21,

2001. Colello allegedly told Goldstein that he did not feel blatantly suicidal,

but did admit to thinking about it. Dr. Goldstein recommended hospitalization,

and asked permission to talk with the patient’s father, Victor Colello. Victor

reportedly told Goldstein that his son was very depressed and seemed to have

lost his desire to live. The father went on to report that Geno could not

cope with seeing Diana date another man, and that Geno had considered harming

the young man. Geno later signed himself in as a voluntary patient at Northridge

Hospital Medical Center on the evening of June 21, 2001. The next morning

Dr. Goldstein received a call from Victor Colello, advising that the hospital

would soon release Geno. Dr. Goldstein telephoned the admitting psychiatrist

and urged him to keep Geno under observation for the weekend. The psychiatrist

declined and discharged Geno, who had no further contact with Dr. Goldstein.

On June 23, 2001, Geno Colello shot Keith Ewing to death and then killed himself

with the same handgun.

Ewing’s parents filed a wrongful death suit naming Goldstein as one of the

defendants (Ewing v. Goldstein, 2004), alleging he had a duty to warn

their son of the risk posed by Geno Colello. A judge granted summary dismissal

of the case against Goldstein, who asserted that his patient never actually

disclosed a threat directly to him. The California Court of Appeals, however,

reinstated the case noting, “When the communication of a serious threat of physical

violence is received by the therapist from the patient’s immediate family, and

is shared for the purpose of facilitating and furthering the patient’s treatment,

the fact that the family member is not technically a ‘patient,’ is not crucial…”

The court noted that psychotherapy does not occur in a vacuum and that therapists

must learn contextual aspects of a patient’s history and personal relationships

to be successful. The court opined that communications from patients’ family

members in this context constitutes a “patient communication.” Requiring mental health professionals to heed warnings from third parties (e.g., a parent or spouse), puts them in the difficult position of assessing the credibility of individuals they do not know (Eisner, 2006; Greer, 2005).

Case 19:

Jan DeMeerleer, a 39 year old mechanical engineer, murdered his ex-fiance Rebecca Schiering and her nine year old son Philip, attempted to murder Schiering's older son, Brian Winkler, and later committed suicide. Psychiatrist Howard Ashby, M.D. had treated DeMeerleer in outpatient psychotherapy for nine years prior to the attack. According to Dr. Ashby’s records, DeMeerleer had expressed suicidal and homicidal ideation, but never named Schiering or her children as potential victims. The Washington State Supreme Court held that Dr. Ashby and DeMeerleer shared a special relationship and that relationship required Dr. Ashby to act with reasonable care, consistent with the standards of the mental health profession, to protect foreseeable victims of DeMeerleer.

This decision appears to significantly broaden the duty that mental health professionals in the State of Washington have to protect and warn potential victims of violence by a patient under their care. This expansive extension of the Tarasoff doctrine to any possible victim, even one not specifically identified by the patient, does not currently extend beyond the state of Washington. The decision creates a new category of "medical negligence," in that state.

With respect to actual risk to public safety, little hard data exist to demonstrate

that warnings effectively prevent harm, although reasonable indirect evidence

does suggest that treatment can prevent violence. Obviously, ethical principles

preclude direct empirical validation of management strategies that may or may

not prevent people at a high risk from doing harm to others (Otto 2000; Litwack

2001; Douglas and Kropp 2002). In addition, violent behavior does not constitute

an illness or mental disorder per se. We cannot treat the violent behavior,

but we can treat a number of clinical variables associated with elevated risks

of violence, including depression, substance abuse, and unmoderated anger (Otto

2000; Douglas and Kropp 2002).

State laws vary as to how or whether a duty of care to third parties pertains (Benjamin, Kent, & Sirikantraporn, 2009). Many psychotherapists remain unaware of the laws in their jurisdictions. They may misinterpret a duty to warn possible victims as the only recourse (Pabian, Welfel, & Beebe, 2009). Alternative options that may be protective include increasing the frequency of communications and sessions, minimizing environmental enablers or other elements that may encourage violent behavior, medication alterations, voluntary hospitalization, commitment, involving other support systems or family members, “do-no-harm” contracts, and consultation with colleagues (Shapiro & Smith, 2011).

HIV and AIDS

Therapists should remain current regarding medical data, treatments, transmission

risks, interventions, and state laws regarding professional interactions with

HIV patients. Thanks to advances in medical care, HIV infection has become a chronic life-threatening condition, as opposed to the more rapidly fatal illness at the outset of the AIDS epidemic. Still, it remains a very hazardous medical condition and many state laws enacted to protect the confidentiality of HIV-infected people and the safety of their sexual partners remain in force. Therapists should speak openly and directly with clients about

dangers of high-risk behaviors. Individuals who are putting others at risk typically

have emotional conflicts about this behavior and may ultimately feel grateful

for a therapist's attention to the difficult issue (Stein, Freedberg et al.

1998; Anderson and Barret 2001; VandeCreek and Knapp 2001). If the client continues

to resist informing partners or using safe practices, clinical judgment becomes

a key issue in assessing the duty to protect (Alghazo, Upton, & Cioe, 2011; Hook & Cleveland, 1999; Palma

& Iannelli, 2002). After exhausting other options, the therapist may have

to breach confidentiality to warn identified partners; however, one should first

notify the client, explain the decision, and seek permission. The client may

agree to go along with the notification. Once again, such case patterns constitute

an occasion to consult colleagues and attorneys and to make certain that prejudices

do not drive the decision.

Psychotherapists who work with clients infected with the human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV) or who have developed acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

must consider additional issues with respect to confidentiality and reporting

obligations (Parry & Mauthner, 2004; VandeCreek and Knapp 2001). McGuire,

Nieri, Abbott, Sheridan, and Fisher (1995) studied the relationship between

therapist's beliefs and ethical decision-making when working with HIV positive

clients who refuse to warn sexual partners or use safe sex practices. The study

focused on psychologists licensed in Florida because of a state law mandating

HIV-AIDS education. Although homophobia rated low among psychologists

sampled, increases in homophobia linked significantly to the likelihood of breaching

confidentiality in AIDS-related cases. This finding suggests that some

degree of prejudice may drive behavior in these circumstances.

Imminent Danger and Confidentiality

At one time, the APA's “Ethical Principles of Psychologists” (APA, 1981) authorized

the disclosure of confidential material without the client's consent only “in

those unusual circumstances in which not to do so would result in clear danger

to the person or others.” As a reflection of the legal developments reported

here, the current APA “Code of Conduct” notes: “Psychologists disclose confidential

information without the consent of the individual only as mandated by law, or

where permitted by law for a valid purpose such as to (1) provide needed professional

services; (2) obtain appropriate professional consultations; (3) protect the

client/patient, psychologist, or others from harm; or (4) obtain payment for

services from a client/patient, in which instance disclosure is limited to the

minimum that is necessary to achieve the purpose” (APA 10: 4.05b). Consider

these case examples:

Case 20:

Bernard Bizzie, LMHC, was about to leave for the weekend when he received

an emergency call from a client, who claimed to have taken a number of pills

in an attempt to kill herself. Bizzie told her to contact her physician and

to come in to see him at 9:00 A.M. on Monday morning. He made no other attempt

to intervene, reasoning that contacting others on her behalf would breach

confidentiality. The client died later that evening without making any other

calls for assistance.

Dr. Bizzie clearly behaved in an unethical and negligent manner by not attending

more directly to his client's needs. Even those rare mental health professionals

who once asserted that one should never disclose confidential information without

the consent of the client in the early post-Tarasoff era (e.g., Dubey, 1974;

Siegel, 1979) or those who still advocate “absolute” confidentiality (Karon

& Widen, 1998) would not likely counsel inaction in the face of such a risk.

There are many steps Bizzie could have taken short of violating the client's

confidentiality. Most obviously, he should have attempted (at the very least)

to learn her location and assure himself that help would reach her if he could

not. Although suicidal threats or gestures may prove manipulative rather than

representing a genuine risk at times, only a foolish and insensitive colleague

would ignore them or attempt to pass them off glibly to another.

Case 21:

Mitchell Morose, age 21, received therapy from Ned Novice, a psychology

intern at a university counseling center. Morose had felt increasingly depressed

and anxious about academic failure and dependency issues with respect to his

family. During one session, Morose told Novice that he had contemplated suicide,

had formulated a plan to carry it out, and was working on a note that he would

leave “to teach my parents a lesson.” Novice attempted to convince Morose

to enter a psychiatric hospital for treatment in view of these feelings, but

Morose accused Novice of “acting like my parents” and left the office. Novice

immediately called George Graybeard, Psy.D., his supervisor, for advice. Graybeard

agreed with Novice about the risk of suicide, and, acting under a provision

of their state's commitment law, they contacted Morose's parents, who could

legally seek an emergency involuntary hospitalization as his next of kin.

Novice told the parents only that he had treated their son who experienced

suicidal ideation, and that he had refused hospitalization. The parents then

assisted in having their son committed for treatment. Following discharge,

Morose filed an ethical complaint against Novice and Graybeard for violating

his confidentiality, especially by communicating with his parents.

Mr. Novice certainly had reason for concern and discussed the matter with his

supervisor. (As an aside, we must assume that, early in their work together,

Novice had explained his “intern” status to Morose, including the fact that

he would routinely discuss the case with his supervisor.) Novice had attempted

to ensure the safety of his client through voluntary hospitalization, but the

client declined. Because the state laws, well known to Dr. Graybeard, provided

a mechanism that called for the involvement of next of kin, the decision to

contact the parents was not inappropriate, despite going against the client's

wishes. Morose had provided ample reason for Novice to consider him at risk,

and the responsible parties disclosed only those matters deemed absolutely necessary

to ensure his safety (i.e., that he seemed at risk for suicide and refused hospitalization).

The therapist did not give the parents details or other confidential material.

In the end, Morose's confidence was indeed violated, and he felt angry. Under

the circumstances, however, Novice and Graybeard behaved in an ethically appropriate

fashion. Later in this course we address specific federal legislation intended

to protect the privacy of health care records (i.e., HIPAA). However, even the

most protective of these regulations permits limited breaches of confidentiality

necessary to provide appropriate treatment.

The best approach to avoiding such problems in one’s practice involves

three separate issues. First, each practitioner should clearly advise every

client at the start of their professional relationship of limits on confidentiality.

Second, clinicians should think through and come to terms with the circumstances

under which they will breach confidentiality or privilege. Consultation with

an attorney about the law in the relevant practice jurisdiction will prove crucial

because of diverse case law decisions and variable statutes. Finally, should

an actual circumstance arise bearing on these issues, consultation with colleagues

can help sort out alternatives that may not come to mind initially.